Downbeat - May 23, 1978

Mr. Feel Good

by Herb Nolan

Mr. Feel Good

by Herb Nolan

It was the worst Chicago night of the year. A sub-zero wind was driving snow like stinging particles of glass over ice-glazed streets. No kidding around, nobody in his right mind would venture out into this arctic nonsense - it hurt to walk half a block. But, yes, there are things in this world that will compel people to resist adversity.

Out in front of a 700 seat theater-club people numb beyond shivering are lining up for the first of four completely sold out Chuck Mangione concerts. Before the night is over, his music will warm them up and his departure will prompt a standing ovation. It might as well be spring.

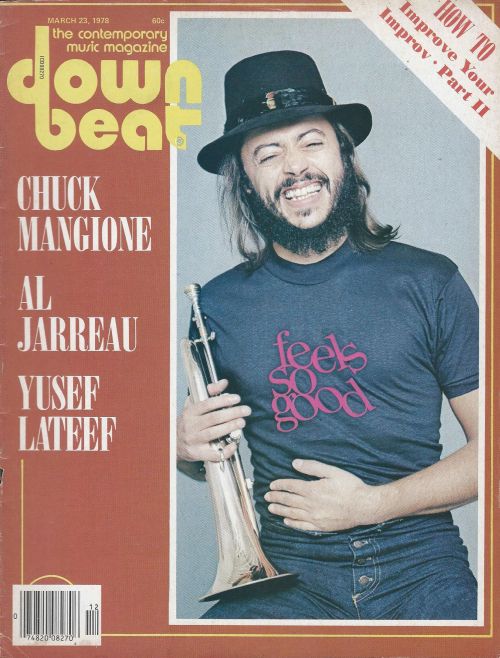

The following afternoon (in the midst of this two-day Windy City engagement) Mangione sits on a couch in a large hotel suite blowing soft, easy notes through his fluegelhorn. Even here in a well-appointed room that seems too big for his diminutive, low-key presence he wears his trademark, a floppy hat.

"Well, we've been working a lot," he says, letting that monumental understatement fall with whimsical nonchalance.

He put his horn down on the cushion next to him and shrugged good-naturedly. "I'm always flabbergasted when I see a sellout house that seats 700 people. Tonight both shows are sold out in advance.... I feel good about it," he said looking as though he doesn't quite understand. "I don't know how it's all happening, but I think it's a combination of things we've been doing for a long time."

Chuck Mangione's band hasn't changed that much from the days when he was playing small jazz clubs instead of concert halls, except for the addition of a guitar. It is essentially an acoustic jazz band playing Mangione's tunes. Some are old ones like Legend Of A One-Eyed Sailor and Land Of Make Believe, others are recent adds like Feels So Good and the theme music from The Children Of Sanchez. It's simply Chuck Mangione, a musician who came up playing with bands like Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, being Chuck Mangione, a performer who probably brings more jazz to more people than any other.

"We work nine months out of the year - that's what we do - and there aren't many bands that do that; I think that's been our biggest salvation because the cuts on our records are long and that kind of handicaps our accessibility through the media.

"I also think the music is very accessible, I like that about the music. I never was one who enjoyed music you had to have a dictionary to understand. Simplicity is something I really think is important in anything.

"Our music always has a strong melodic content. I think that's one thing that appeals to people. It's very rhythmic, which is one of the first things people can relate to. When you get people going away from a group like ours and they're remembering a melody you've got something happening that a lot of other performers don't have. If a person isn't into improvisation at least he can sit there and wait for the melody to return. On the other hand, those people who are really into that part of it can get off on it because the cats in the band can play. So when people leave a concert they don't just leave saying 'Well, the saxophone player was incredible' or 'the drummer was terrific.' They'll remember the music too.

"It's a wonderful band to be in," Mangione said about his current group, which includes Chris Vadala on reeds and flutes, gutarist Grant Geissman, bassist Charles Meeks and 19-year-old drummer James Bradley, Jr. "It's the youngest band I've had and yet they are not just good for being young. They're strong players and they love to play. There's a positive feeling all the time. To do two hours twice a night is not an easy thing, but with this band it doesn't sound tired.

"The biggest change has been the addition of the guitar," he continued. "It fattens up the small band sound and gives me a chance to play my horn. I was starting to write myself out of the music; I used to get up from the piano to play the horn and I'd feel that there was a lot of space there. I began spending more and more time at the piano instead of playing my horn.

"When I did the Main Squeeze album I played a lot of horn on it. Consequently, when I went out to play in public I knew I wanted to have a guitar. And it's worked out real nice. I feel good with that instrument in the band. I think that's been the biggest change in what's happened with our music.

"Our audience is coming from so many different directions," Chuck said about the broad appeal of his music. "If you look at the people in our audiences you'll see a conglomeration of everything. I think it's because our music appears in a lot of places where other peoples' music that's kind of related to ours doesn't. We had an incredible amount of television exposure over the past year; we were on the Johnny Carson show a couple of times and we were on this Las Vegas Awards show.... "

It's hard to forget the incongruous image of Chuck Mangione on a huge Vegas-glitter stage wearing his floppy hat and surrounded by a glitzy showgirl chorus line. "You know I wasn't even playing, it was all lip sync."

"I used to be very turned around by television but once you understand what television is - what its purpose is - I mean it's not an album, it's not a concert, it's a certain amount of time to get as much music out so you can give people a taste of what you do. It's a positive step to get that kind of exposure. Another thing that's happening is that our music is played by drum and bugle corps and marching bands at football games. It's coming out of all these different places so the audience is coming from everywhere."

Part of Mangione's appeal as a performer is his own presence, which communicates a positive enthusiasm with subtle dimensions and a boyish innocence. He understands that you can demand an audience's attention for two hours, so long as you don't hit them too hard too often with your music.

"I think I learned a lot from watching Dizzy when I was young. I've seen a lot of musicians whom I really love, but he was the first guy who just let people know he was having a good time. He would introduce guys in the band, tell people what he was going to play and he was loose.

"People don't go out to have a bad time, they go out to enjoy themselves. And making people feel comfortable just makes it easier, because if they get the message they give it right back to you and you get that feeling going between you and them - it really makes it happen.

"l love to play for people. I don't know how musicians live that always play for microphones that puts stuff on tape, that in turn puts stuff on records. I need to play for people; I have to feel that music going through them. I know so many wonderful musicians, in fact great musicians, who are playing ... the least challenging music. They're just into content - doing jingles - because that's where the money is, in residuals and things like that. There are guys playing on a lot of records and they don't even hear the end product. They are just laying a track and then they leave and they don't know what's going on top of it or what's happening later. To me the music is never complete until somebody hears it.

"I think there's something happening in this world that's real bad," Mangione said, letting the subject drift to something that had been on his mind all along. "It's this feeling that people should retire when they are 55, which means, I guess, that after you are 28 years old it's all over. You're halfway there already and you have to start thinking about getting out instead of getting in - work four days a week, everybody should sleep 12 hours a day, then get a massage for four hours and go see your shrink, and after that lay back some more in the evening. Wouldn't it have been wonderful if they had retired Duke Ellington or Pablo Casals when they were 55? That would have made a lot of sense, right?

"I think the world is falling asleep and the music is included," he continued. "We did a movie score, The Children Of Sanchez, and I want to tell you that proved to me what we could really do - what people can do when they extend themselves.... All the musicians I was working with were going beyond anything that had ever happened to them before as far as just physical endurance goes. All we had was three weeks to get the music done, so I booked a studio for three weeks 24 hours a day and we rotated engineers. It got to be kind of an intense period and I was driving everybody crazy just whipping people to keep it going as fast as I could because only I knew how much we had to get done in three weeks. We made it and some really nice music came out of it. I'm pleased.

"Whatever the picture turns out to be, I think it stimulated in me a lot of feelings that l remember from a long time ago when I was a kid - family experiences, religious experiences and just things I related to very strongly. So I really knew this picture right away. I don't think I could have done it in three weeks if it wasn't that way - it was really a very emotional involvement.

"It was over Labor Day when I did the music for the film. I locked myself in a hotel room for three days. It was the first time, I think, in a lot of years that I spent three days totally involved with no interruptions. After those three days I knew exactly where the highway was going and where to get off.

"When I compose," he said about his art, "sometimes an idea will happen quickly. Other times it just won't come out, you get to a certain point and get stuck; when that happens I'll put the thing away and leave it and sometimes it takes a lot of years before it gets done. This is the first time I have had to write music against the clock, and it was sort of satisfying to see that it could be done - that I could do it - but it's not my favorite way of doing it."

Mangione glanced over at his horn. "I feel good about playing this thing again, it's like Sparky Lyle, the relief pitcher for the New York Yankees. He used to say the more he pitches the more he feels comfortable and the stronger he gets. Well, I feel more comfortable with my instrument now that I'm playing a lot."

In recent years Chuck Mangione has been performing with large symphony orchestras, as well as touring a couple of times a year with a large ensemble of his own. At first the ensemble utilized strings, but now he's using a unit with four french horns, four trombones, three trumpets, a reed section with everybody doubling, and the quintet. He says that the problem with strings was that all the time was spent trying to get the 12 strings properly heard, and as a result the music suffered. It would have taken 40 to 50 strings to make things work correctly.

Besides playing and conducting with orchestras like the Hamilton Philharmonic, Mangione does clinics with high school orchestras.

"I think young musicians are rarely challenged today. They never find out what's really out there in the real world. A lot of people who do clinics with high school kids like to send the music weeks ahead of time so everybody's learned it by rote before the clinician even gets there. Then he comes along, talks to them a little bit, they run the tune down and do a concert. Nobody has really learned anything.

"Well, what I do is I don't send the music ahead of time. We walk in the day before the concert is scheduled and we pass out the same music we play with the Rochester Orchestra or the Hamilton or stuff I have recorded with studio people in New York or L.A. I bring in Jeff Tyzik to play lead trumpet and put my group in the middle. The kids find out fast about where they are; they find out about reading - whether they can really read. They find out about playing in tune and about endurance, and the illusions about people just getting together, hanging out and rehearsing for days goes out the window. When you are in a studio, paying all that money for the room and the musicians, nobody is waiting for anybody to get it together.

"I used to teach courses on how to ride a bus and how to check into an airport. No kidding, there's so much missing from reality in relationship to young musicians and where they are going that somebody has to tell them what's coming."

One of the things that might be coming if they become as popular as Mangione is criticism. It can come like a jealous husband after a suspect wife - "What the hell you been doin' that got you so popular all of sudden." Mangione's music, for example, has been dismissed by some as something like "bubblegum jazz" with the content of a Bazooka wrapper cartoon.

"Yeah, we get some critical abuse," he commented, "and I get very bugged with the fact that jazz musicians or critics would be so negative about something so positive. Look, Herbie Hancock, George Benson, Stanley Turrentine, us, Chick, Weather Report - I think that music has touched a lot of people. So maybe the critics' favorite tune of Herbie's is not Chameleon. But think of all the people who went out and not only bought that album, but went back to find out about Herbie Hancock and found Miles and Donald Byrd and a lot of other musicians. It's the same with George Benson. People just don't buy the one record that just happened, they go back and look for other things that person has done. It's terrific that young people are getting introduced to the music. Wouldn't it be awful if you could hear Herbie, George Benson or Chick Corea everyday on Top 40 radio? It would be wonderful!"

Mangione looked as if he'd just had a vision of a jazz Disneyland, full of brand new rides that nobody had been on before that could turn you on just as fast as the old ones. "When Cannonball Adderley did Mercy, Mercy, Mercy people said he'd sold out. How does somebody sell out? If they could figure it out and computerize music, we wouldn't need any musicians. They can't. I don't think any body can sit down and say, 'I'm going to write a hit tune' and 'This is going to make me change' and 'I'll sell out and I'll crossover' and all that nonsense - it doesn't happen that way. When I can find 19-year-old kids that play the drums, that means somebody is doing something that's reaching those young people. "You know to me, good or bad, criticism is only one person's point of view. The only problem is that thousands of people read that one point of view as if it's news - factual stuff. But as long as they keep putting your name in print and are interested in you as a person and a musician, then it's happening.

"What drives me crazy, what makes me angry, is when people treat you less and give you less than what you should be given as a human being - I'm talking about respect and dignity. I just can't handle it when people have no pride in what they're doing.

"We deal with service all the time - airlines, limos, hotels - and it seems like we are approaching an age of total indifference. People have been beat upon for so long that I think we are teaching them to become computers. If you as a human being feel degraded, then I'm in trouble, too. If you don't have pride in what you are doing, then you shouldn't be doing it. I get mad and I Get Mad.

"When I tell a limo driver I think he's driving too fast and he doesn't care enough about his own life to drive a little slower, I can get awful mad. If I'm in a studio and the equipment is falling apart, and I am paying an incredible amount of money for that room and there ain't nobody who cares about it, I can get awful mad. When a security guard won't let me in the door of my own concert because he's got nothing to do with anything, I can get real mad.

"I don't enjoy beating people up, but the more you stroke people and tell them you love them the more they tend to fall asleep. I just have very little tolerance for people who don't love themselves. I do have a Sicilian temper." Chuck Mangione is a musician of broad, diverse talents. He's a conductor, composer, teacher, bandleader and performer without fragmenting his talents to the point where the substance is minimal and the art an illusion. He says he loves all the things he does for different reasons.

"I think the most fun is playing with a small band because it's loose and every night is a new night. There's also a physical release that I love, it is a lot of something coming out of you through that horn, airwise and person-wise. I like to feel tired at the end of the night for having done that, rather than from having done something nonphysical.

"I love to conduct an orchestra, I like to see all those people putting all that energy in one direction. Of course, writing to me is the most lasting aspect of music you can hang on to; you can put it on record and have it forever.

"People say 'Why do you have a band?'" he continued. "I have a band that plays music that I write. I don't think I would be a bandleader as such just to stand up there in front of a group - that's not what I want to do. I have a group specifically to play music that I write.

"I don't think there are that many bands today," he added, "I really don't. I am a little disappointed in musicians in general for wanting to seek a comfortable environment and never move and take their music out to the people. We don't have bands anymore, we have an artist who puts a group together and goes out for two months a year to support an album that just came out. I know why musicians stay at home. Travel isn't easy and it's expensive. But I think the answer to everything is for people to hear live music. That's what music is all about.

"When I was growing up there were all kinds of bands out there. In Rochester, New York, of all places, there were two clubs going six nights a week, with a Sunday afternoon matinee.

"Anyhow, I wish there were more bands happening, taking music to the people, playing it on a regular basis. It would be better for everybody, but there aren't any bands. I can't find any bands.

"My goal is to play the music and get it to as many people as possible - to keep playing the music I believe in. There are still a lot of places to take the music, and I am enjoying it, I am enjoying playing, I like the band, I like the music, people feel good, and the record company feels good. l'm not looking to get out."

Out in front of a 700 seat theater-club people numb beyond shivering are lining up for the first of four completely sold out Chuck Mangione concerts. Before the night is over, his music will warm them up and his departure will prompt a standing ovation. It might as well be spring.

The following afternoon (in the midst of this two-day Windy City engagement) Mangione sits on a couch in a large hotel suite blowing soft, easy notes through his fluegelhorn. Even here in a well-appointed room that seems too big for his diminutive, low-key presence he wears his trademark, a floppy hat.

"Well, we've been working a lot," he says, letting that monumental understatement fall with whimsical nonchalance.

He put his horn down on the cushion next to him and shrugged good-naturedly. "I'm always flabbergasted when I see a sellout house that seats 700 people. Tonight both shows are sold out in advance.... I feel good about it," he said looking as though he doesn't quite understand. "I don't know how it's all happening, but I think it's a combination of things we've been doing for a long time."

Chuck Mangione's band hasn't changed that much from the days when he was playing small jazz clubs instead of concert halls, except for the addition of a guitar. It is essentially an acoustic jazz band playing Mangione's tunes. Some are old ones like Legend Of A One-Eyed Sailor and Land Of Make Believe, others are recent adds like Feels So Good and the theme music from The Children Of Sanchez. It's simply Chuck Mangione, a musician who came up playing with bands like Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, being Chuck Mangione, a performer who probably brings more jazz to more people than any other.

"We work nine months out of the year - that's what we do - and there aren't many bands that do that; I think that's been our biggest salvation because the cuts on our records are long and that kind of handicaps our accessibility through the media.

"I also think the music is very accessible, I like that about the music. I never was one who enjoyed music you had to have a dictionary to understand. Simplicity is something I really think is important in anything.

"Our music always has a strong melodic content. I think that's one thing that appeals to people. It's very rhythmic, which is one of the first things people can relate to. When you get people going away from a group like ours and they're remembering a melody you've got something happening that a lot of other performers don't have. If a person isn't into improvisation at least he can sit there and wait for the melody to return. On the other hand, those people who are really into that part of it can get off on it because the cats in the band can play. So when people leave a concert they don't just leave saying 'Well, the saxophone player was incredible' or 'the drummer was terrific.' They'll remember the music too.

"It's a wonderful band to be in," Mangione said about his current group, which includes Chris Vadala on reeds and flutes, gutarist Grant Geissman, bassist Charles Meeks and 19-year-old drummer James Bradley, Jr. "It's the youngest band I've had and yet they are not just good for being young. They're strong players and they love to play. There's a positive feeling all the time. To do two hours twice a night is not an easy thing, but with this band it doesn't sound tired.

"The biggest change has been the addition of the guitar," he continued. "It fattens up the small band sound and gives me a chance to play my horn. I was starting to write myself out of the music; I used to get up from the piano to play the horn and I'd feel that there was a lot of space there. I began spending more and more time at the piano instead of playing my horn.

"When I did the Main Squeeze album I played a lot of horn on it. Consequently, when I went out to play in public I knew I wanted to have a guitar. And it's worked out real nice. I feel good with that instrument in the band. I think that's been the biggest change in what's happened with our music.

"Our audience is coming from so many different directions," Chuck said about the broad appeal of his music. "If you look at the people in our audiences you'll see a conglomeration of everything. I think it's because our music appears in a lot of places where other peoples' music that's kind of related to ours doesn't. We had an incredible amount of television exposure over the past year; we were on the Johnny Carson show a couple of times and we were on this Las Vegas Awards show.... "

It's hard to forget the incongruous image of Chuck Mangione on a huge Vegas-glitter stage wearing his floppy hat and surrounded by a glitzy showgirl chorus line. "You know I wasn't even playing, it was all lip sync."

"I used to be very turned around by television but once you understand what television is - what its purpose is - I mean it's not an album, it's not a concert, it's a certain amount of time to get as much music out so you can give people a taste of what you do. It's a positive step to get that kind of exposure. Another thing that's happening is that our music is played by drum and bugle corps and marching bands at football games. It's coming out of all these different places so the audience is coming from everywhere."

Part of Mangione's appeal as a performer is his own presence, which communicates a positive enthusiasm with subtle dimensions and a boyish innocence. He understands that you can demand an audience's attention for two hours, so long as you don't hit them too hard too often with your music.

"I think I learned a lot from watching Dizzy when I was young. I've seen a lot of musicians whom I really love, but he was the first guy who just let people know he was having a good time. He would introduce guys in the band, tell people what he was going to play and he was loose.

"People don't go out to have a bad time, they go out to enjoy themselves. And making people feel comfortable just makes it easier, because if they get the message they give it right back to you and you get that feeling going between you and them - it really makes it happen.

"l love to play for people. I don't know how musicians live that always play for microphones that puts stuff on tape, that in turn puts stuff on records. I need to play for people; I have to feel that music going through them. I know so many wonderful musicians, in fact great musicians, who are playing ... the least challenging music. They're just into content - doing jingles - because that's where the money is, in residuals and things like that. There are guys playing on a lot of records and they don't even hear the end product. They are just laying a track and then they leave and they don't know what's going on top of it or what's happening later. To me the music is never complete until somebody hears it.

"I think there's something happening in this world that's real bad," Mangione said, letting the subject drift to something that had been on his mind all along. "It's this feeling that people should retire when they are 55, which means, I guess, that after you are 28 years old it's all over. You're halfway there already and you have to start thinking about getting out instead of getting in - work four days a week, everybody should sleep 12 hours a day, then get a massage for four hours and go see your shrink, and after that lay back some more in the evening. Wouldn't it have been wonderful if they had retired Duke Ellington or Pablo Casals when they were 55? That would have made a lot of sense, right?

"I think the world is falling asleep and the music is included," he continued. "We did a movie score, The Children Of Sanchez, and I want to tell you that proved to me what we could really do - what people can do when they extend themselves.... All the musicians I was working with were going beyond anything that had ever happened to them before as far as just physical endurance goes. All we had was three weeks to get the music done, so I booked a studio for three weeks 24 hours a day and we rotated engineers. It got to be kind of an intense period and I was driving everybody crazy just whipping people to keep it going as fast as I could because only I knew how much we had to get done in three weeks. We made it and some really nice music came out of it. I'm pleased.

"Whatever the picture turns out to be, I think it stimulated in me a lot of feelings that l remember from a long time ago when I was a kid - family experiences, religious experiences and just things I related to very strongly. So I really knew this picture right away. I don't think I could have done it in three weeks if it wasn't that way - it was really a very emotional involvement.

"It was over Labor Day when I did the music for the film. I locked myself in a hotel room for three days. It was the first time, I think, in a lot of years that I spent three days totally involved with no interruptions. After those three days I knew exactly where the highway was going and where to get off.

"When I compose," he said about his art, "sometimes an idea will happen quickly. Other times it just won't come out, you get to a certain point and get stuck; when that happens I'll put the thing away and leave it and sometimes it takes a lot of years before it gets done. This is the first time I have had to write music against the clock, and it was sort of satisfying to see that it could be done - that I could do it - but it's not my favorite way of doing it."

Mangione glanced over at his horn. "I feel good about playing this thing again, it's like Sparky Lyle, the relief pitcher for the New York Yankees. He used to say the more he pitches the more he feels comfortable and the stronger he gets. Well, I feel more comfortable with my instrument now that I'm playing a lot."

In recent years Chuck Mangione has been performing with large symphony orchestras, as well as touring a couple of times a year with a large ensemble of his own. At first the ensemble utilized strings, but now he's using a unit with four french horns, four trombones, three trumpets, a reed section with everybody doubling, and the quintet. He says that the problem with strings was that all the time was spent trying to get the 12 strings properly heard, and as a result the music suffered. It would have taken 40 to 50 strings to make things work correctly.

Besides playing and conducting with orchestras like the Hamilton Philharmonic, Mangione does clinics with high school orchestras.

"I think young musicians are rarely challenged today. They never find out what's really out there in the real world. A lot of people who do clinics with high school kids like to send the music weeks ahead of time so everybody's learned it by rote before the clinician even gets there. Then he comes along, talks to them a little bit, they run the tune down and do a concert. Nobody has really learned anything.

"Well, what I do is I don't send the music ahead of time. We walk in the day before the concert is scheduled and we pass out the same music we play with the Rochester Orchestra or the Hamilton or stuff I have recorded with studio people in New York or L.A. I bring in Jeff Tyzik to play lead trumpet and put my group in the middle. The kids find out fast about where they are; they find out about reading - whether they can really read. They find out about playing in tune and about endurance, and the illusions about people just getting together, hanging out and rehearsing for days goes out the window. When you are in a studio, paying all that money for the room and the musicians, nobody is waiting for anybody to get it together.

"I used to teach courses on how to ride a bus and how to check into an airport. No kidding, there's so much missing from reality in relationship to young musicians and where they are going that somebody has to tell them what's coming."

One of the things that might be coming if they become as popular as Mangione is criticism. It can come like a jealous husband after a suspect wife - "What the hell you been doin' that got you so popular all of sudden." Mangione's music, for example, has been dismissed by some as something like "bubblegum jazz" with the content of a Bazooka wrapper cartoon.

"Yeah, we get some critical abuse," he commented, "and I get very bugged with the fact that jazz musicians or critics would be so negative about something so positive. Look, Herbie Hancock, George Benson, Stanley Turrentine, us, Chick, Weather Report - I think that music has touched a lot of people. So maybe the critics' favorite tune of Herbie's is not Chameleon. But think of all the people who went out and not only bought that album, but went back to find out about Herbie Hancock and found Miles and Donald Byrd and a lot of other musicians. It's the same with George Benson. People just don't buy the one record that just happened, they go back and look for other things that person has done. It's terrific that young people are getting introduced to the music. Wouldn't it be awful if you could hear Herbie, George Benson or Chick Corea everyday on Top 40 radio? It would be wonderful!"

Mangione looked as if he'd just had a vision of a jazz Disneyland, full of brand new rides that nobody had been on before that could turn you on just as fast as the old ones. "When Cannonball Adderley did Mercy, Mercy, Mercy people said he'd sold out. How does somebody sell out? If they could figure it out and computerize music, we wouldn't need any musicians. They can't. I don't think any body can sit down and say, 'I'm going to write a hit tune' and 'This is going to make me change' and 'I'll sell out and I'll crossover' and all that nonsense - it doesn't happen that way. When I can find 19-year-old kids that play the drums, that means somebody is doing something that's reaching those young people. "You know to me, good or bad, criticism is only one person's point of view. The only problem is that thousands of people read that one point of view as if it's news - factual stuff. But as long as they keep putting your name in print and are interested in you as a person and a musician, then it's happening.

"What drives me crazy, what makes me angry, is when people treat you less and give you less than what you should be given as a human being - I'm talking about respect and dignity. I just can't handle it when people have no pride in what they're doing.

"We deal with service all the time - airlines, limos, hotels - and it seems like we are approaching an age of total indifference. People have been beat upon for so long that I think we are teaching them to become computers. If you as a human being feel degraded, then I'm in trouble, too. If you don't have pride in what you are doing, then you shouldn't be doing it. I get mad and I Get Mad.

"When I tell a limo driver I think he's driving too fast and he doesn't care enough about his own life to drive a little slower, I can get awful mad. If I'm in a studio and the equipment is falling apart, and I am paying an incredible amount of money for that room and there ain't nobody who cares about it, I can get awful mad. When a security guard won't let me in the door of my own concert because he's got nothing to do with anything, I can get real mad.

"I don't enjoy beating people up, but the more you stroke people and tell them you love them the more they tend to fall asleep. I just have very little tolerance for people who don't love themselves. I do have a Sicilian temper." Chuck Mangione is a musician of broad, diverse talents. He's a conductor, composer, teacher, bandleader and performer without fragmenting his talents to the point where the substance is minimal and the art an illusion. He says he loves all the things he does for different reasons.

"I think the most fun is playing with a small band because it's loose and every night is a new night. There's also a physical release that I love, it is a lot of something coming out of you through that horn, airwise and person-wise. I like to feel tired at the end of the night for having done that, rather than from having done something nonphysical.

"I love to conduct an orchestra, I like to see all those people putting all that energy in one direction. Of course, writing to me is the most lasting aspect of music you can hang on to; you can put it on record and have it forever.

"People say 'Why do you have a band?'" he continued. "I have a band that plays music that I write. I don't think I would be a bandleader as such just to stand up there in front of a group - that's not what I want to do. I have a group specifically to play music that I write.

"I don't think there are that many bands today," he added, "I really don't. I am a little disappointed in musicians in general for wanting to seek a comfortable environment and never move and take their music out to the people. We don't have bands anymore, we have an artist who puts a group together and goes out for two months a year to support an album that just came out. I know why musicians stay at home. Travel isn't easy and it's expensive. But I think the answer to everything is for people to hear live music. That's what music is all about.

"When I was growing up there were all kinds of bands out there. In Rochester, New York, of all places, there were two clubs going six nights a week, with a Sunday afternoon matinee.

"Anyhow, I wish there were more bands happening, taking music to the people, playing it on a regular basis. It would be better for everybody, but there aren't any bands. I can't find any bands.

"My goal is to play the music and get it to as many people as possible - to keep playing the music I believe in. There are still a lot of places to take the music, and I am enjoying it, I am enjoying playing, I like the band, I like the music, people feel good, and the record company feels good. l'm not looking to get out."