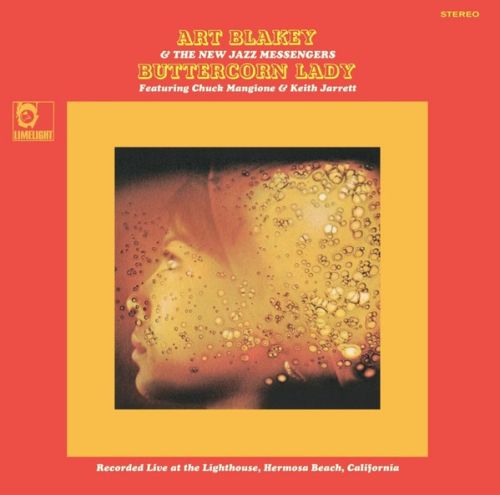

Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers

Featuring Chuck Mangione & Keith Jarrett

Chuck Mangione - Trumpet

Frank Mitchell - Tenor Sax

Keith Jarrett - Piano

Reggie Johnson - Bass

Art Blakey - Drums

Featuring Chuck Mangione & Keith Jarrett

Chuck Mangione - Trumpet

Frank Mitchell - Tenor Sax

Keith Jarrett - Piano

Reggie Johnson - Bass

Art Blakey - Drums

- Buttercorn Lady *

- Recuerdo *

- The Theme

- Between Races *

- My Romance

- Secret Love

Recorded live January, 1966 at The Lighthouse, Hermosa Beach, CA

Emarcy Records 822 471-2

* Written by Chuck Mangione

Re-released as Get The Message

Emarcy Records 822 471-2

* Written by Chuck Mangione

Re-released as Get The Message

Liner Notes from the EmArcy CD release:

For more than three decades Art Blakey has been introducing new young jazz talent to the world. The list of notable musicians who have come to prominence in his bands includes, among many others, Clifford Brown, Horace Silver, Lee Morgan, Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, and more recently, of course, Wynton Marsalis. Heard on this CD is a short-lived mid-60's edition of Blakey's Messengers which included two musicians who later went on to achieve huge international success -trumpeter Chuck Mangione and pianist Keith Jarrett. Also featured here is Frank Mitchell, an obscure but excellent tenor saxophonist who later recorded for Blue Note with Lee Morgan.

Leonard Feather's liner notes from the original 1966 Limelight issue of this session follow:

"Yes, sir, I'm going to stay with the youngsters - it keeps the mind active.

The comment by Art Blakey sounds typical of the man who calls himself "the world's youngest jazz drummer. Interestingly enough, the remark was not made recently. It was quoted in this writer's liner notes for an album Blakey recorded ten years ago. Then 36, already able to boast half a lifetime devoted to music, he was speaking of men in his group who were eight or ten years his junior. Today, a long way from senility and still charged with the same indomitable fervor, Art can make the same comment when the sidemen are young enough to be his children.

The present edition of the New Messengers, introduced here for the first time on records, is hot off the presses, having been edited by Blakey since his last recording deadline. It is an entirely new unit, one that maintains Blakey's unbroken record for replacing the seemingly irreplaceable. By now he has had as many sets of Messengers as Herman has had Herds. After so many years gone by, and so many messages successfully delivered, it has become clear that Art's ability to surround himself with brilliant new talents is to be credited less to good fortune than to a permanently Wide-open pair of ears.

"It was time for a change;' says Art of the events that led to the new turnover." Sometimes you find there are problems involved in getting the guys to work together, spiritually as well as musically. And it's no use making replacements by just going back to the same old clique. You have to watch out constantly for new sounds, new faces. I don't want any group of mine to sound like a carbon copy of the one before it. We have to have our own identity, with fresh concepts, a feeling that the men can get along with one another, and a general eagerness to go forward.

The reorganization got under way in the summer of 1965 in Atlantic City, N.J. The front line was changed first. After Lee Morgan and Art had agreed to go their separate ways, the vacancy thus created seemed like an unusually rough one to fill particularly when one could go through piles of earlier Blakey records and find men like Clifford Brown, Kenny Dorham and Freddie Hubbard in the lead role.

It was Dizzy Gillespie, an early friend of Blakey's and a colleague in their Billy Eckstine band days, who came up with the suggestion that solved Art's problem. "Remember Chuck Mangione?" said Diz, and not too many days had elapsed before Art was sure that the reminder had been an invaluable one.

Charles Frank Mangione was born in Rochester, N.Y, November 29, 1940. His older brother Gaspare (Gap), is a pianist-arranger and was co-leader from 1960-64 of their Jazz Brothers group. Chuck's extensive music studies, which began when he was eight, included trumpet piano and theory at the Eastman School of Music. He received his Bachelor of Music degree, with a major in music education, in 1963.

"My father is a jazz fan and was a major factor in my musical development;' says Chuck."When I was too young to get into nightclubs alone, he'd introduce me to any name jazzman who visited town. As a result I got to sit with Art Blakey and Dizzy, among others, and Diz presented me with an 'up-do' horn. All musicians were welcome at our house for dinner and Italian wine; Diz and Art are still close friends of my father.

Frank Mitchell, the bristling new tenor saxophonist from the Bronx, is even more of a newcomer to the big time than Mangione. Art recalls: "One night I was off the bandstand and Art Jr., my son, was playing in my place, when Frank asked if he could sit in. I heard this sound and before I saw who it was I thought I was listening to Wayne Shorter! He writes, too, and he's going to be important - watch him.

There should be plenty of time to watch him, for as these words went to press Mitchell was still some 81 years short of his 100th birthday.

The prime conversation piece in the new group, for most listeners, has been Keith Jarrett the incredibly advanced young pianist who was born in Allentown, Pa., May 8, 1945. The eldest of five musically inclined brothers, he was playing at three and concertizing professionally at seven. In 1962 he played a two-hour solo concert consisting entirely of his own extended works for solo piano. "Then I went to Boston;' he says, to spend a year at Berklee School of Music on a scholarship. For three years I had a trio which was, I think, my most important vehicle for expression up to the present. After Boston, I moved to New York and worked with Roland Kirk, C Sharpe (the alto player) and Tony Scott.

Completing the group is bassist Reggie Johnson, who had played a few gigs with Art Jr. The latter brought him to an Art Sr. rehearsal one day, and as the young-old man put it, "He reminded me of Jymie Merritt and I knew he'd be right for us." Johnson, born December 13, 1940 in Owensboro, Ky., started as a trombonist and gained most of his musical experience playing in various Army bands over a six-year period. He took up bass in 1961 and by 1964-65 was working with such groups as Archie Shepp, Roland Kirk, Warren Covington, Giuseppe Logan and Sun Ra. He names Ray Brown, Paul Chambers and Ron Carter as his major influences.

The Lighthouse is a 180-seater room at sea level, on Pier Avenue in Hermosa Beach, Calif., literally a stone's throw from the Pacific Ocean. Howard Rumsey the bassist of the original Stan Kenton orchestra, walked in there one afternoon in 1949 and saw John Levine, the owner, with a small group of customers. He persuaded Levine to let him organize a Sunday session.

The success of the first session led to a series, then to a full weekend jazz policy and soon to a week-long musical diet, using the best West Coast jazz talent. Throughout the years since then, under Rumsey's astute guidance, the Lighthouse has weathered the same storms that have caused most of the other jazz clubs to founder. It is now in its 17th year of successful operation and its fifth as a locus operandi for nationally known jazz combos. In other words, it is the longest-established night club in the U.S.A. using modern jazz regularly.

"A lot of the credit for the success of this album should go to the Lighthouse;' says Art Blakey. "Being a musician himself, Howard Rumsey knows how to take care of musicians who work for him. Little things like ice-water and a comfortable couch in the dressing rooms, as well as big things like having a good piano and sound system - add it all up and you can see why this is one of the few places where it's a genuine pleasure to work.

The preceding information concerning the new Blakey battalion and the recording location should not be construed to mean that the relentless beat and musical muscle of the New Messengers cannot still be credited in large measure to the catalytic force of the leader. No matter how great Art's talent for finding other talent, the New Messengers would falter in pace and shrivel in value if the Messenger-in-Chief were not still there, incisively and polyrhythmically at the helm. It might be appropriate, in fact, to amend Blakey's statement of ten years ago by making it read, even more fittingly: "Yes, sir, I'm going to stay with the youngsters - it keeps their minds active:'

SIDE ONE: Chuck Mangione's Buttercorn Lady is a very proper melody, in the sense that is is quite diatonic and adheres to the 32-bar formula. If you were typecasting you might have to classify it as Calypso; at all events, there is a certain Caribbean flavor and an unmistakable melodic charm to the composition, and a fitting simplicity to much of Keith Jarrett's solo. The latter, because of the nature of this theme, gives us only a slight taste of his talent; for the entire Keith Jarrett, wait until Side Two.

Recuerdo, which my Latin teacher tells me is Spanish for I Remember, is a splendid study in mood-building. Mangione, who wrote it, introduces it in a muted minor-mode, Milesish style and soon moves into a long solo passage that offers soulful evidence of his fast-maturing talent. Note the effective role of Reggie Johnson's montuna-Iike bass lines.

Frank Mitchell helps to compound the intensity with a brooding, building improvisation that leads into a fascinating sequence by Jarrett. The latter uses a technique currently fashionable in jazz, in which the pianist leans over (or walks around) into the piano's belly and gently strokes it by the strings. The piano responds by purring softly. Later, back at the keyboard, Jarrett also evokes a pensively beautiful mood.

Toward the end the leader takes over. Blakey's respect for the beat has never been more evident than in this unusual excursion, for despite the variety of devices employed there is a triplet accent virtually all the way through his solo.

Chuck returns for the concluding statement, with discreet fills by Frank Mitchell. Incidentally, though the composition seems to have a Gillespieish quality, it was not originally planned that way. "I wrote it, says Mangione, "as a 'legit' work scored for brass and percussion.

And from there it's back to the theme, or The Theme if you wish to be formal.

This little riff, known through the years by a variety of titles, has long served as the sign-off for Art's and other combos. Basically it is a very simple work, but not too simple to enable young Mr. Jarrett to make something refreshingly original out of his solo.

SIDE TWO: Between Races is a hard-bop type theme recorded a while back by Maynard Ferguson, for whom Mangione worked before joining Blakey. This track is especially noteworthy for the contribution of Frank Mitchell. Although everyone (including Chuck) plays a valuable role in making this passage meaningful and exciting, the credit still belongs to Mitchell for a solo that mixes inspiration with coordination. Blakey takes command with total authority during most of the couple of minutes between Mitchell's solo and the reprise of the theme.

My Romance is a durable melody which, my Richard Rodgers Fact Book tells me, was introduced in a show called Jumbo at the New York Hippodrome in 1935. Somehow it sounds a little different at the Hermosa Beach Lighthouse in 1966. It is Chuck's vehicle almost all the way; slow on the first chorus and doubled up (but still in the same reflective groove) on the second. Before his final half-chorus there is a remarkable Keith Jarrett interlude. Keith says "I have no favorites; anyone who is sincere as an artist and as a person is influential to me;' and from his solo one can deduce that he has listened attentively to everyone from Art Tatum and Bud Powell to Bill Evans and McCoy Tyner.

Secret love is a 1954 song by the ASCAP veteran Sammy Fain. It is a favorite of Chuck's; he recorded it in the first Jazz Brothers album back in 1960. The tempo is off-to-the-races, and with Art's furious drive as a guiding force they demonstrate that few other combos, if any, can better meet the challenge of a heady pace like this. There is a fine display of walking by Reggie Johnson, admirable Shorterish tenor from Frank, and a completely unbelievable Keith Jarrett solo that will show you what we meant by remarking that Buttercorn Lady gave only a limited idea of the range of his ideas and technique.

Leonard Feather

For more than three decades Art Blakey has been introducing new young jazz talent to the world. The list of notable musicians who have come to prominence in his bands includes, among many others, Clifford Brown, Horace Silver, Lee Morgan, Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, and more recently, of course, Wynton Marsalis. Heard on this CD is a short-lived mid-60's edition of Blakey's Messengers which included two musicians who later went on to achieve huge international success -trumpeter Chuck Mangione and pianist Keith Jarrett. Also featured here is Frank Mitchell, an obscure but excellent tenor saxophonist who later recorded for Blue Note with Lee Morgan.

Leonard Feather's liner notes from the original 1966 Limelight issue of this session follow:

"Yes, sir, I'm going to stay with the youngsters - it keeps the mind active.

The comment by Art Blakey sounds typical of the man who calls himself "the world's youngest jazz drummer. Interestingly enough, the remark was not made recently. It was quoted in this writer's liner notes for an album Blakey recorded ten years ago. Then 36, already able to boast half a lifetime devoted to music, he was speaking of men in his group who were eight or ten years his junior. Today, a long way from senility and still charged with the same indomitable fervor, Art can make the same comment when the sidemen are young enough to be his children.

The present edition of the New Messengers, introduced here for the first time on records, is hot off the presses, having been edited by Blakey since his last recording deadline. It is an entirely new unit, one that maintains Blakey's unbroken record for replacing the seemingly irreplaceable. By now he has had as many sets of Messengers as Herman has had Herds. After so many years gone by, and so many messages successfully delivered, it has become clear that Art's ability to surround himself with brilliant new talents is to be credited less to good fortune than to a permanently Wide-open pair of ears.

"It was time for a change;' says Art of the events that led to the new turnover." Sometimes you find there are problems involved in getting the guys to work together, spiritually as well as musically. And it's no use making replacements by just going back to the same old clique. You have to watch out constantly for new sounds, new faces. I don't want any group of mine to sound like a carbon copy of the one before it. We have to have our own identity, with fresh concepts, a feeling that the men can get along with one another, and a general eagerness to go forward.

The reorganization got under way in the summer of 1965 in Atlantic City, N.J. The front line was changed first. After Lee Morgan and Art had agreed to go their separate ways, the vacancy thus created seemed like an unusually rough one to fill particularly when one could go through piles of earlier Blakey records and find men like Clifford Brown, Kenny Dorham and Freddie Hubbard in the lead role.

It was Dizzy Gillespie, an early friend of Blakey's and a colleague in their Billy Eckstine band days, who came up with the suggestion that solved Art's problem. "Remember Chuck Mangione?" said Diz, and not too many days had elapsed before Art was sure that the reminder had been an invaluable one.

Charles Frank Mangione was born in Rochester, N.Y, November 29, 1940. His older brother Gaspare (Gap), is a pianist-arranger and was co-leader from 1960-64 of their Jazz Brothers group. Chuck's extensive music studies, which began when he was eight, included trumpet piano and theory at the Eastman School of Music. He received his Bachelor of Music degree, with a major in music education, in 1963.

"My father is a jazz fan and was a major factor in my musical development;' says Chuck."When I was too young to get into nightclubs alone, he'd introduce me to any name jazzman who visited town. As a result I got to sit with Art Blakey and Dizzy, among others, and Diz presented me with an 'up-do' horn. All musicians were welcome at our house for dinner and Italian wine; Diz and Art are still close friends of my father.

Frank Mitchell, the bristling new tenor saxophonist from the Bronx, is even more of a newcomer to the big time than Mangione. Art recalls: "One night I was off the bandstand and Art Jr., my son, was playing in my place, when Frank asked if he could sit in. I heard this sound and before I saw who it was I thought I was listening to Wayne Shorter! He writes, too, and he's going to be important - watch him.

There should be plenty of time to watch him, for as these words went to press Mitchell was still some 81 years short of his 100th birthday.

The prime conversation piece in the new group, for most listeners, has been Keith Jarrett the incredibly advanced young pianist who was born in Allentown, Pa., May 8, 1945. The eldest of five musically inclined brothers, he was playing at three and concertizing professionally at seven. In 1962 he played a two-hour solo concert consisting entirely of his own extended works for solo piano. "Then I went to Boston;' he says, to spend a year at Berklee School of Music on a scholarship. For three years I had a trio which was, I think, my most important vehicle for expression up to the present. After Boston, I moved to New York and worked with Roland Kirk, C Sharpe (the alto player) and Tony Scott.

Completing the group is bassist Reggie Johnson, who had played a few gigs with Art Jr. The latter brought him to an Art Sr. rehearsal one day, and as the young-old man put it, "He reminded me of Jymie Merritt and I knew he'd be right for us." Johnson, born December 13, 1940 in Owensboro, Ky., started as a trombonist and gained most of his musical experience playing in various Army bands over a six-year period. He took up bass in 1961 and by 1964-65 was working with such groups as Archie Shepp, Roland Kirk, Warren Covington, Giuseppe Logan and Sun Ra. He names Ray Brown, Paul Chambers and Ron Carter as his major influences.

The Lighthouse is a 180-seater room at sea level, on Pier Avenue in Hermosa Beach, Calif., literally a stone's throw from the Pacific Ocean. Howard Rumsey the bassist of the original Stan Kenton orchestra, walked in there one afternoon in 1949 and saw John Levine, the owner, with a small group of customers. He persuaded Levine to let him organize a Sunday session.

The success of the first session led to a series, then to a full weekend jazz policy and soon to a week-long musical diet, using the best West Coast jazz talent. Throughout the years since then, under Rumsey's astute guidance, the Lighthouse has weathered the same storms that have caused most of the other jazz clubs to founder. It is now in its 17th year of successful operation and its fifth as a locus operandi for nationally known jazz combos. In other words, it is the longest-established night club in the U.S.A. using modern jazz regularly.

"A lot of the credit for the success of this album should go to the Lighthouse;' says Art Blakey. "Being a musician himself, Howard Rumsey knows how to take care of musicians who work for him. Little things like ice-water and a comfortable couch in the dressing rooms, as well as big things like having a good piano and sound system - add it all up and you can see why this is one of the few places where it's a genuine pleasure to work.

The preceding information concerning the new Blakey battalion and the recording location should not be construed to mean that the relentless beat and musical muscle of the New Messengers cannot still be credited in large measure to the catalytic force of the leader. No matter how great Art's talent for finding other talent, the New Messengers would falter in pace and shrivel in value if the Messenger-in-Chief were not still there, incisively and polyrhythmically at the helm. It might be appropriate, in fact, to amend Blakey's statement of ten years ago by making it read, even more fittingly: "Yes, sir, I'm going to stay with the youngsters - it keeps their minds active:'

SIDE ONE: Chuck Mangione's Buttercorn Lady is a very proper melody, in the sense that is is quite diatonic and adheres to the 32-bar formula. If you were typecasting you might have to classify it as Calypso; at all events, there is a certain Caribbean flavor and an unmistakable melodic charm to the composition, and a fitting simplicity to much of Keith Jarrett's solo. The latter, because of the nature of this theme, gives us only a slight taste of his talent; for the entire Keith Jarrett, wait until Side Two.

Recuerdo, which my Latin teacher tells me is Spanish for I Remember, is a splendid study in mood-building. Mangione, who wrote it, introduces it in a muted minor-mode, Milesish style and soon moves into a long solo passage that offers soulful evidence of his fast-maturing talent. Note the effective role of Reggie Johnson's montuna-Iike bass lines.

Frank Mitchell helps to compound the intensity with a brooding, building improvisation that leads into a fascinating sequence by Jarrett. The latter uses a technique currently fashionable in jazz, in which the pianist leans over (or walks around) into the piano's belly and gently strokes it by the strings. The piano responds by purring softly. Later, back at the keyboard, Jarrett also evokes a pensively beautiful mood.

Toward the end the leader takes over. Blakey's respect for the beat has never been more evident than in this unusual excursion, for despite the variety of devices employed there is a triplet accent virtually all the way through his solo.

Chuck returns for the concluding statement, with discreet fills by Frank Mitchell. Incidentally, though the composition seems to have a Gillespieish quality, it was not originally planned that way. "I wrote it, says Mangione, "as a 'legit' work scored for brass and percussion.

And from there it's back to the theme, or The Theme if you wish to be formal.

This little riff, known through the years by a variety of titles, has long served as the sign-off for Art's and other combos. Basically it is a very simple work, but not too simple to enable young Mr. Jarrett to make something refreshingly original out of his solo.

SIDE TWO: Between Races is a hard-bop type theme recorded a while back by Maynard Ferguson, for whom Mangione worked before joining Blakey. This track is especially noteworthy for the contribution of Frank Mitchell. Although everyone (including Chuck) plays a valuable role in making this passage meaningful and exciting, the credit still belongs to Mitchell for a solo that mixes inspiration with coordination. Blakey takes command with total authority during most of the couple of minutes between Mitchell's solo and the reprise of the theme.

My Romance is a durable melody which, my Richard Rodgers Fact Book tells me, was introduced in a show called Jumbo at the New York Hippodrome in 1935. Somehow it sounds a little different at the Hermosa Beach Lighthouse in 1966. It is Chuck's vehicle almost all the way; slow on the first chorus and doubled up (but still in the same reflective groove) on the second. Before his final half-chorus there is a remarkable Keith Jarrett interlude. Keith says "I have no favorites; anyone who is sincere as an artist and as a person is influential to me;' and from his solo one can deduce that he has listened attentively to everyone from Art Tatum and Bud Powell to Bill Evans and McCoy Tyner.

Secret love is a 1954 song by the ASCAP veteran Sammy Fain. It is a favorite of Chuck's; he recorded it in the first Jazz Brothers album back in 1960. The tempo is off-to-the-races, and with Art's furious drive as a guiding force they demonstrate that few other combos, if any, can better meet the challenge of a heady pace like this. There is a fine display of walking by Reggie Johnson, admirable Shorterish tenor from Frank, and a completely unbelievable Keith Jarrett solo that will show you what we meant by remarking that Buttercorn Lady gave only a limited idea of the range of his ideas and technique.

Leonard Feather