Downbeat - May 8, 1975

An Open Feeling, A Sound Of Love

by Lee Underwood

An Open Feeling, A Sound Of Love

by Lee Underwood

When, in that inimitable style of his, W.C. Fields said, "My boy, you can't cheat an honest man," he probably meant a man like Chuck Mangione, who will not be ideologically derailed nor psychologically tricked.

During our conversation, for example, I relayed a string of flowery compliments to him, and then turned around and relayed some devastatingly searing criticisms (see below). Through it all, and throughout the entire interview, he remained involved, but detached & intense, but calm; radiant, but restrained. He is a naturally complete and integrated man, not unheard of in today's big-gun entertainment world, but rare indeed.

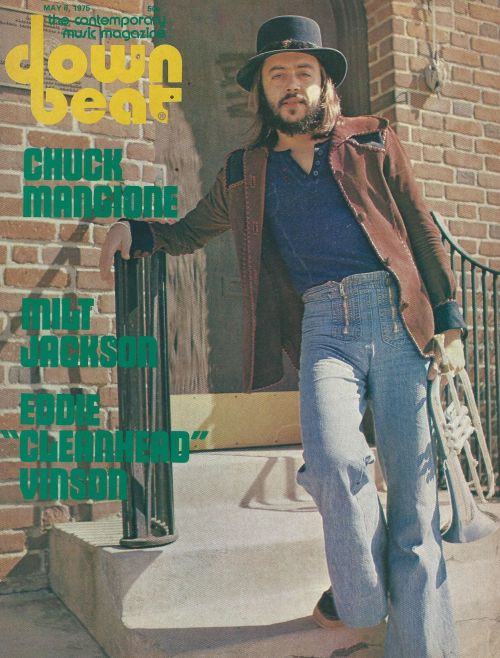

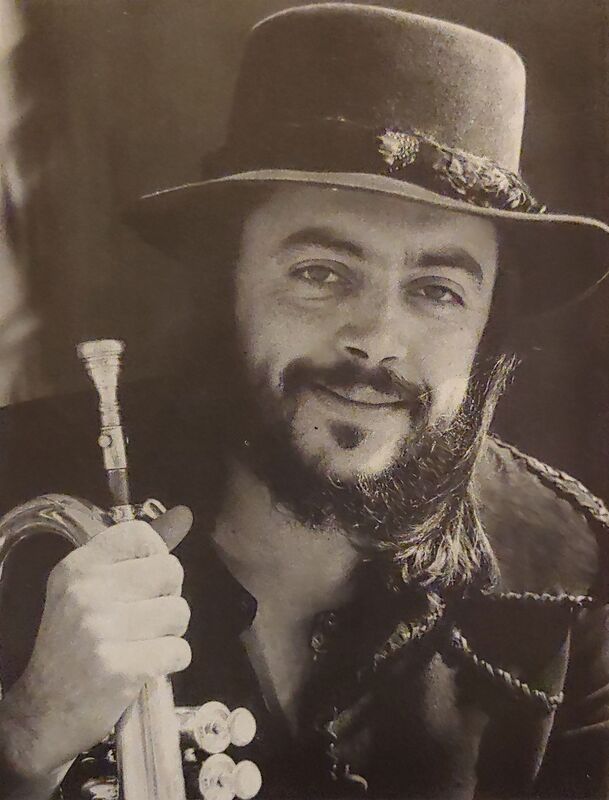

No, he does not sleep with his hat on - although that flat-brimmed headgear has become associated with him almost as closely as his lush and lyrical flugelhorn melodies. The hat made its first appearance in the year 1969, when Chuck was just beginning to feel loose and natural as a musician and as a man. The era of the jazz musician wearing black tie and tails was finally crumbling in Rochester, New York, where Chuck was born in late 1940. "Everybody was uptight with all those tails. That had to be wiped away so musicians could feel free like they naturally feel."

Chuck was gigging at a jazz club called The Shakespeare. It was a club "where music was the fourth reason why people came in. They came to drink, to eat, to socialize, and then to listen to the music." Four hundred people packed that room. The cash registers clanged. People rapped and rapped, and drank, and rapped some more.

But there is a king in every crowd, and every musician soon learns to play to him. In this particular crowd, the king was Bill Tedeschi, who, with his wife Marie, came in night after night specifically to listen to Chuck and his group. The first Quartet album is dedicated to Bill and Marie, "because they listened when no one else did. We knew that they knew where our music was at. It really helped to have them there." When Bill and Marie Tedeschi gave him the now classic hat as a Christmas present, Chuck wore it. The picture that appeared on the cover of that first album, Friends & Love, (Mercury SRM 1-631) became an image.

If the hat were only an image, however - just another record company hype-job - Chuck would not be Chuck Mangione, for Chuck is above all in tune with himself. That hat has instead become a symbol of his own naturalness, of his own extraordinary personal and musical equilibrium. "It became a kind of security blanket for me at first”, he explains, "and then something that belonged with me. Now I love it, and wear it because l want to. It is me. No, this is not the original hat," he adds as an afterthought. "The original has gangrene from three years of over-wear."

Chuck's latest, sixth album finds him switching record labels, from Mercury to A&M. Chase The Clouds Away features one track with Quartet, one track with Quartet and vocalist Esther Satterfield, and four tracks with a 40-man orchestra. "But whether there are 40 guys or four playing, you never lose sight of the Quartet. All the music was done live in the studio. There was no over-dubbing. We were playing eight and nine minute takes with an orchestra, and they were all good. It was like picking between red wine and white wine."

Switching record companies is like switching lovers: teary trauma, followed by purposeful search, hopefully followed by new love. And the new love's attitude is supremely important. "In the past we always had a lot of resistance to doing things the way we wanted to. True, we always managed to pull it off and do it pretty much our way; but to A&M, that's the obvious thing to do.

"A&M is a different world. It doesn't feel like it's one of the most efficient and fast-growing companies in the record business, but it is. I'm amazed anything gets done around here. I mean, when you walk in and talk with the guard at the gate, there's no paranoia, there's nobody drawing a gun. Everybody knows everybody, and it's a very relaxed situation. For us to be able to come all the way across the country and walk into a studio situation and immediately feel at home has been a revelation."

It was crucial to Mangione that A&M's relaxed atmosphere be reflected in contractual black-and-white. "When I spoke to Jerry Moss about becoming associated with A&M, my most important question was, “How do you look at me as a person totally committed to writing his own music and recording it'?” l have no interest in having a producer come in and say, if you do this and this and this, you're gonna be commercially successful, and then you can do whatever you want. “I mean, who wants to be successful on the basis of something you don't love”? I think the worst thing you can do is devise something other people will love but that you hate, something you will have to play every day and every night.

"A&M's response was, we will decide on a budget. You will go into the studio, and you will come out, and you will hand us a tape and say, "This is my next album."' There was never any discussion of what was I going to do, or why didn't I tell them about it first and then we'll see. It was just book the time, hire the people, do the job."

Featuring Gerry Niewood on soprano, tenor and flute, Chip Jackson on bass, and Joe LaBarbera on drums, the Chuck Mangione Quartet today hovers on the shimmering verge of superstardom. In the recent downbeat Readers' Poll, Chuck placed in no fewer than six categories (including Jazz Group, Jazzman, Arranger, Composer).

One reason the Chuck Mangione Quartet is gaining such enthusiastic response is because "we're made up of four very sympathetic musicians. You write music, and all of a sudden you're hearing it the way you conceived it originally--three other people. Just giving it back to you without any instructions. Everybody in the band is a monster on his own individual instrument.

"Gerry Niewood and I grew up together in the same neighborhood, and went to the same schools together in Rochester. I started playing at eight, he at ten. We were both committed to music at early ages, although he did go to Buffalo University to major in Business Administration. Then he went to Eastman School of Music for four years. That's when we really became involved, because he was playing in the Eastman Jazz Ensemble when I was directing it, that was also about the time I was forming my own Quartet. As a result, we were spending a lot of musical time together. I picked Gerry for the Quartet because of his flexibility. He doesn't just double on an instrument - when he picks up the flute, he owns it. When he plays the soprano, that's his instrument.

"Our bass player, Chip Jackson, has been with the band only about six months. He's the most melodic bass player I've ever played with. I can have a musical conversation with him when I'm playing fluegelhorn, and that's important to me. When I get up from the keyboard, and all of a sudden that harmonic thing is gone, I don't miss it with him: he has a way of picking the notes that set up all the overtones, and the music sounds full. And as a soloist, he's incredible.

"Our drummer, Joe LaBarbera, is a very unusual drummer: he gives my music a flow that it's never had before, and he's capable of moving very comfortably from the small Quartet context into a large, 40-piece orchestra situation. Joey is definitely a drummer whose ego is not harmfully involved. He's not possessed with showing the way, with directing the band he wants to be, and is capable of being, a part of the situation."

Each member of Chuck Mangione's quartet must be highly skilled both as an ensemble player and as a soloist, and each must be able to fit into the family. "lt's more than a musical situation. You have to fall in love with the person. In the music of this band, you can feel that everybody came there to play together. I consider us to be one of the few bands playing together today. There are a lot of groups where a star stands out front and shines while three or four other people do something around him, but they're not really a team, not really a band that's making music as a unit. I'm very proud of this group as a group, as a family. In this band, there is no fear. We've built a situation where we can react to each other. When it gets to that relaxed and comfortable place where everybody is really into it, you never count measures, and you never worry if this guy is gonna be right there. You can just lay back and let it happen."

For many years, Chuck Mangione played with the predominate thought, "How good was I tonight?" He was concerned only secondarily with the overall sound of the music, the total success of the entire band, and the degree of audience communication.

"But you can't live very long on that. It's a shallow existence, and very unrewarding, l imagine even Hank Aaron felt there were only a few of all those home runs that meant a whole lot to him. If you're honest with yourself, you're not going to have that many special nights as an individual. I really depend on Gerry, Chip and Joe to make my music sound good. People have said weird things, like “You should never give that much solo space or attention to somebody else.” Well, man, some of the greatest players in the world are standing up there! They should play, and the people should hear them!"

Chuck lived all but two and a half of his 34 years in Rochester. His older brother, Gap, was also a musician (piano), and "he bought all the records." Chuck took his degree in Eastman, taught in parochial school for one year, then moved to New York City for the two and a half years.

His grandparents were Italian immigrants. His father formed the bridge between Old Italy and New America. He is a rare and special man, a man "totally committed to us, to his kids. He grew up just wanting his children to have the opportunities he never had." Most of all, Chuck's father allowed him and the others to truly be themselves. He never tried to force them into artificial roles of middle-class respectability.

Mr. Mangione owned a grocery store that was attached to the house. "He used to sit in the kitchen eating supper, and would run out to take care of a customer. It was a very friendly neighborhood-family situation. He would open up the store at 6:30 in the morning, finish at 11:30 at night, and then say, “What do you guys want to do? Where do you want to go?”

It wasn't as if he had initially been a music freak. He loves music - and he's the greatest dancer in the world - but he was never a frustrated musician. He wanted only for us. If we had been interested in medicine, he would have taken us to hospitals to see what was happening. But we were interested in music, so he said, "Who do you want to hear ?"

"And we would go hear somebody like Dizzy Gillespie. Father would walk up to them like he knew them all his life, and he'd say, “Hi, Dizzy! My name is Mr. Mangione, these are my kids, they play.” And before you'd know it, my father would be talking with this guy, and would invite them over for spaghetti and Italian wine, and we'd wind up having a jam session in the living room.

"Now that I think about the musicians in that house, I freak out, you know'? One afternoon there were Jimmy Cobb, Sam Jones, Junior Mance, Ronnie Zito, and Ron Carter, and we were all sitting there in my living room playing! This would happen every week. Musicians would come into town, we'd go and meet then, they'd be invited over for food, and we'd get to play."

Dizzy Gillespie also came over to the house, but I don't think he came over and played, as much as he came over and ate! We got to be really good friends, and he sent me one of those upswept horns of his. I regard him as being my musical father. He was truly an inspiration for me."

When Chuck was a boy, big bands were in - Stan Kenton, Count Basie, Woody Herman, etc. Later, he listened to beboppers Art Blakey, Cannonball Adderly. Horace Silver, Miles Davis, and Gillespie.

When he graduated from high school and attended the Eastman School of Music, "there was absolutely nothing happening there in the musical directions I wanted to follow. Jazz was forbidden. We had to rehearse in hidden corners, you know?" However, Chuck feels he was perhaps a bit narrow-minded at the time. "I did what a lot of young people do when something is not their way: I rebelled against everything. Because of that, I didn't really take advantage of the four years I spent as an Eastman student. I never studied composition, and I never studied orchestration - the very things that would have been extremely beneficial to me today.

"As it stands now, both composing and arranging are very tedious processes for me, and orchestration is a big guessing game. It's actually sitting down at the piano and pounding out voicings and trying to imagine what they will sound like. I've been very lucky. The music sounds good, and I don't apologize for anything I've recorded, but I've nevertheless been very, very lucky.

"When you're 17 or 18, you think you know all the answers - who you'll spend the rest of your life with, your religious beliefs, and exactly what you're going to be. Very positive. I was gonna be a bebop player in a jazz club. I would have committed anybody to an insane asylum who walked up to me and said, “Pretty soon you're gonna have a chance to conduct the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra.” I keep trying to tell young people to stay open to everything - music, people, feelings. To not become narrow. If you put up a shield like I did, there's no chance to learn anything, to grow."

Mangione himself later taught at the Eastman School of Music, directing the Eastman Jazz Ensemble. "When I arrived, there was only one jazz ensemble. When I left, there was a studio orchestra, a film writing course, an improvisation course, and three jazz ensembles.''

From 1960 to 1963, Chuck and Gap - The Mangione Brothers - recorded three Riverside albums: The Jazz Brothers, Hey, Baby!, and Spring Fever. Chuck also cut an album on his own, Recuerdo, for Jazzland Records.

He went to New York in 1964, freelanced with Kai Winding and Maynard Ferguson, and finally landed his boyhood dream gig: trumpet player with Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers. He stayed for nearly three years, playing with Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea who also passed through Blakey's band.

Leaving Rochester to play music was a major decision for Chuck, but an even greater decision came in 1969. At nearly 30 years of age, he finally accepted the fact that he was going to be a musician, "that that was what I was going to be doing for the rest of my life. There was no longer any reason for me to wake up every morning worrying about it, to wake up and say, `Well, how am I doing?' like comparing myself to something on the stock market."

It was in that same year that he composed Kaleidoscope. He hired fifty musicians himself, and put on a concert. That particular concert lost a pile of money, but it also led to his first record, Friends & Love. "The album was never meant to be an album. It wasn't a record date. When we performed it with the Rochester Philharmonic, all we had was a four-track tape recorder there to back up the PBS television unit that was taping it."

When it was all over, Chuck was amazed with the quality of the compositions. "I couldn't believe that nobody else was ever going to hear this music!" He borrowed seven thousand dollars from the bank, hired and paid the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, and went into the record business himself. "Everything good that's happened to us has been motivated by ourselves. We released Friends & Love locally by ourselves, just the way it finally came out of Mercury. When it started making noises in Upstate New York, Mercury came up and signed us to a four year contract."

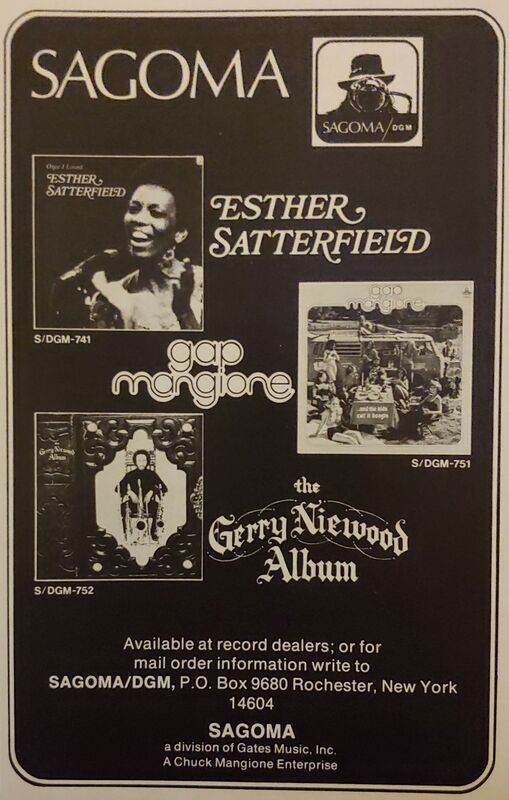

Since that time, Hill Where The Lord Hides (from Friends) was nominated for a Grammy as Best Instrumental. His first Quartet album was nominated for Best Small Group Jazz Performance. This year, Land of Make Believe was up for two Grammies: Best Big Band Performance, and Best Instrumental Arrangement Accompanying a Vocalist (Esther Satterfield). Chuck has also created his own mail order record company, Sagoma, and has signed Gerry Niewood, Gap, and Esther Satterfield.

He does not care for teaching jazz clinics, "because everything is memorized ahead of time, and there's no education experience." But he does love teaching. The week before our talk, he had been teaching high school kids in San Francisco. "Most young people today don't get challenged. Everybody gives them the one book, the one pill, the one philosophy that's going to give them all the answers. They want to make a million dollars in six months and then get out of music.

"I think the great thing about this last week was that I saw a lot of young people fall in love with music. To me, that's the only reason to be in music, because you can't count on anything else besides that love affair. That's always gotta be going on. You gotta be prepared to scuffle financially and to sacrifice a lot of very basic things in life. I wouldn't have it any other way. You can go to some professional orchestras, and it's a fight to get those people to remember that they love music. To them, it's a factory gig. They're watching the clock, time to stop, take a break, back on, toot-toot-toot, gimme the money, go home. It can be a very painful experience to somebody who really loves music."

Chuck feels it was a lesson for those kids to see him and the other Quartet members load their own equipment. “I'm not ashamed of it, either," he says. "We don't have a roadie. That means that we leave for airports early, and haul the electric piano and bass and drums ourselves. Nobody baby sits for us. We'd rather do it that way, so we can keep playing the music we believe in. We could obviously make more bread by going in another musical direction. But we would rather forego the luxury of somebody else breaking their back for us than to pay the bread and then maybe have to compromise." Transportation costs keep climbing; clubs are not getting any bigger; and Chuck will not play the acoustically abhorrent hockey rinks. "I don't make good money yet," Chuck says quite honestly, "but I make a living and pay the rent and support my wife and two daughters. I do think there is another financial level that we will reach soon, and that will make things more comfortable for everybody."

Some people have called Chuck Mangione a "renaissance musician," and others have been even more florid in their appreciation. Many musicians hunger for such praises, and even base their entire existences on it. But Chuck maintains, "A critic's reaction is just the reaction of another human being. If he's a good critic, he's human in what he hears, and he reacts, and he does what he has to do. I read all of those things, and I know they're very important, because a lot of people read criticism as fact, rather than as one person's opinion."

Despite the pressures attending his very bright future, Chuck Mangione has maintained his psychological equilibrium so well that hostile remarks don't phase him any more than compliments.

One critic called his orchestral concerts "an emasculated, homogenized stab at mixing muzak with funk." An acquaintance of mine, Edouard, attended the Royce Hall concert with me. He was scathing in his criticism. "My God," he said. "Mangione goes for the medium-rare in everything he does. I don't know, perhaps he's a flash in the pan and has lost his magic. Maybe he's come down with a severe case of the Minnie Ripertons. Sure, he plays poignant melodies that, quote, 'generate a kind of haunting Swiss Alps feeling' - it's just another way of saying he's the suburbanite housewife's dream of a white Miles Davis. I mean, who cares?

"His sexuality has all of the rage and passion of a Continental breakfast," Edouard continued to rant. "Let's face it: Chuck Mangione's audience came to be lulled and caressed, to be held close to mama's breast, to be lovingly patted all over with Johnson's Musical Baby Powder. He picks up his horn and spills out Cream of Wheat laced with dollar signs. He is the balls and banner of the entire toast and tea set. That's who cares."

How do you deal with criticism like this, Chuck?

"I don't have to deal with it. That's one person's opinion of a situation. They're certainly entitled to that opinion."

Come on, now.

"I'm just knocked out - and the record is proving it - that wherever we go, people are enjoying the music. And everybody in the band is enjoying it. We're not playing music that we don't have a good time playing. And there's no formula, no attempt to reach a specific audience of any kind. We've just been doing what we do, and the audiences have been getting bigger, and the people are getting off on what we're doing.

But at the same time, Chuck, you got a reaction. That's not somebody who just shrugged his shoulders and said, "So what?" That's somebody who at least was touched by the music. In a way, it's a compliment: Love me, hate me, but react!"

What about that question of blandness?

"Obviously, the music doesn't feel bland to me. I write the music I feel, and I play the music I write. People have the option to call it whatever they want to."

But how do you feel when somebody talks that way about your music?

"Nobody ever likes to hear anybody dislike or object to what they do. I think that sometimes people make comments in which they're trying to be very dramatic in what they say, trying to impress other people with the style of their words. I mean, that's a very well-done piece of material there."

"True ... It's nice to have people react. Five years ago, something like that would probably have destroyed me. If what he said was true to me, I just wouldn't be able to handle it. However, when you reach the point where you're true with yourself and honest with yourself musically, then none of that carries any more weight than what it really is, just criticism. I have to live with myself everyday. I don't have to walk up to that man and explain anything to him. I just do what I do, and do it to the best of my ability. And that's me."

Somebody said you lack presence, that your main emphasis is on the preconceived aspect of the music, like classical music.

"All music that I've ever enjoyed has form . . ."

But where is Chuck?

"If a piece of music is a piece of music, there are parts of it to be played together and played well, and there are parts that leave room for improvisation. If somebody starts out with something so complex and so abstract that his improvisation is no longer abstract or complex by comparison or extension, then how will the people be able to see?

"You see, I've always loved music that had melody, that had good harmonic changes, and that felt good rhythmically. That's the kind of music I want to play. My music has form, but it does not have a formula. I want the music to have a beginning and an end. And I want it to be something so beautiful that when somebody walks out, they don't say, 'Whew! I just heard the greatest technician in the world!' I want people just to say, 'The music felt good.'"

You have a kind of intensity that comes out in those long melodic lines, Chuck, but is there in fact a lack of assertiveness?

"l think this band has more balls than any other band I've ever played with. It has the flexibility and the guts to take its clothes off in front of a thousand people and play music that is very, very simple, and then turn around and play something that is very, very hot at the other extreme.

"You can have a lot of energy, and a lot of enthusiasm, and a lot of intensity, and a lot of guts, but you don't have to be mauling somebody. Nor does it have to be intensity generated through high volume amplifiers. You don't have to throw up. You can be gentle and still be intense.

"I just think of music as being with someone you love, and how you want to be with them. That is what it's all about."

During our conversation, for example, I relayed a string of flowery compliments to him, and then turned around and relayed some devastatingly searing criticisms (see below). Through it all, and throughout the entire interview, he remained involved, but detached & intense, but calm; radiant, but restrained. He is a naturally complete and integrated man, not unheard of in today's big-gun entertainment world, but rare indeed.

No, he does not sleep with his hat on - although that flat-brimmed headgear has become associated with him almost as closely as his lush and lyrical flugelhorn melodies. The hat made its first appearance in the year 1969, when Chuck was just beginning to feel loose and natural as a musician and as a man. The era of the jazz musician wearing black tie and tails was finally crumbling in Rochester, New York, where Chuck was born in late 1940. "Everybody was uptight with all those tails. That had to be wiped away so musicians could feel free like they naturally feel."

Chuck was gigging at a jazz club called The Shakespeare. It was a club "where music was the fourth reason why people came in. They came to drink, to eat, to socialize, and then to listen to the music." Four hundred people packed that room. The cash registers clanged. People rapped and rapped, and drank, and rapped some more.

But there is a king in every crowd, and every musician soon learns to play to him. In this particular crowd, the king was Bill Tedeschi, who, with his wife Marie, came in night after night specifically to listen to Chuck and his group. The first Quartet album is dedicated to Bill and Marie, "because they listened when no one else did. We knew that they knew where our music was at. It really helped to have them there." When Bill and Marie Tedeschi gave him the now classic hat as a Christmas present, Chuck wore it. The picture that appeared on the cover of that first album, Friends & Love, (Mercury SRM 1-631) became an image.

If the hat were only an image, however - just another record company hype-job - Chuck would not be Chuck Mangione, for Chuck is above all in tune with himself. That hat has instead become a symbol of his own naturalness, of his own extraordinary personal and musical equilibrium. "It became a kind of security blanket for me at first”, he explains, "and then something that belonged with me. Now I love it, and wear it because l want to. It is me. No, this is not the original hat," he adds as an afterthought. "The original has gangrene from three years of over-wear."

Chuck's latest, sixth album finds him switching record labels, from Mercury to A&M. Chase The Clouds Away features one track with Quartet, one track with Quartet and vocalist Esther Satterfield, and four tracks with a 40-man orchestra. "But whether there are 40 guys or four playing, you never lose sight of the Quartet. All the music was done live in the studio. There was no over-dubbing. We were playing eight and nine minute takes with an orchestra, and they were all good. It was like picking between red wine and white wine."

Switching record companies is like switching lovers: teary trauma, followed by purposeful search, hopefully followed by new love. And the new love's attitude is supremely important. "In the past we always had a lot of resistance to doing things the way we wanted to. True, we always managed to pull it off and do it pretty much our way; but to A&M, that's the obvious thing to do.

"A&M is a different world. It doesn't feel like it's one of the most efficient and fast-growing companies in the record business, but it is. I'm amazed anything gets done around here. I mean, when you walk in and talk with the guard at the gate, there's no paranoia, there's nobody drawing a gun. Everybody knows everybody, and it's a very relaxed situation. For us to be able to come all the way across the country and walk into a studio situation and immediately feel at home has been a revelation."

It was crucial to Mangione that A&M's relaxed atmosphere be reflected in contractual black-and-white. "When I spoke to Jerry Moss about becoming associated with A&M, my most important question was, “How do you look at me as a person totally committed to writing his own music and recording it'?” l have no interest in having a producer come in and say, if you do this and this and this, you're gonna be commercially successful, and then you can do whatever you want. “I mean, who wants to be successful on the basis of something you don't love”? I think the worst thing you can do is devise something other people will love but that you hate, something you will have to play every day and every night.

"A&M's response was, we will decide on a budget. You will go into the studio, and you will come out, and you will hand us a tape and say, "This is my next album."' There was never any discussion of what was I going to do, or why didn't I tell them about it first and then we'll see. It was just book the time, hire the people, do the job."

Featuring Gerry Niewood on soprano, tenor and flute, Chip Jackson on bass, and Joe LaBarbera on drums, the Chuck Mangione Quartet today hovers on the shimmering verge of superstardom. In the recent downbeat Readers' Poll, Chuck placed in no fewer than six categories (including Jazz Group, Jazzman, Arranger, Composer).

One reason the Chuck Mangione Quartet is gaining such enthusiastic response is because "we're made up of four very sympathetic musicians. You write music, and all of a sudden you're hearing it the way you conceived it originally--three other people. Just giving it back to you without any instructions. Everybody in the band is a monster on his own individual instrument.

"Gerry Niewood and I grew up together in the same neighborhood, and went to the same schools together in Rochester. I started playing at eight, he at ten. We were both committed to music at early ages, although he did go to Buffalo University to major in Business Administration. Then he went to Eastman School of Music for four years. That's when we really became involved, because he was playing in the Eastman Jazz Ensemble when I was directing it, that was also about the time I was forming my own Quartet. As a result, we were spending a lot of musical time together. I picked Gerry for the Quartet because of his flexibility. He doesn't just double on an instrument - when he picks up the flute, he owns it. When he plays the soprano, that's his instrument.

"Our bass player, Chip Jackson, has been with the band only about six months. He's the most melodic bass player I've ever played with. I can have a musical conversation with him when I'm playing fluegelhorn, and that's important to me. When I get up from the keyboard, and all of a sudden that harmonic thing is gone, I don't miss it with him: he has a way of picking the notes that set up all the overtones, and the music sounds full. And as a soloist, he's incredible.

"Our drummer, Joe LaBarbera, is a very unusual drummer: he gives my music a flow that it's never had before, and he's capable of moving very comfortably from the small Quartet context into a large, 40-piece orchestra situation. Joey is definitely a drummer whose ego is not harmfully involved. He's not possessed with showing the way, with directing the band he wants to be, and is capable of being, a part of the situation."

Each member of Chuck Mangione's quartet must be highly skilled both as an ensemble player and as a soloist, and each must be able to fit into the family. "lt's more than a musical situation. You have to fall in love with the person. In the music of this band, you can feel that everybody came there to play together. I consider us to be one of the few bands playing together today. There are a lot of groups where a star stands out front and shines while three or four other people do something around him, but they're not really a team, not really a band that's making music as a unit. I'm very proud of this group as a group, as a family. In this band, there is no fear. We've built a situation where we can react to each other. When it gets to that relaxed and comfortable place where everybody is really into it, you never count measures, and you never worry if this guy is gonna be right there. You can just lay back and let it happen."

For many years, Chuck Mangione played with the predominate thought, "How good was I tonight?" He was concerned only secondarily with the overall sound of the music, the total success of the entire band, and the degree of audience communication.

"But you can't live very long on that. It's a shallow existence, and very unrewarding, l imagine even Hank Aaron felt there were only a few of all those home runs that meant a whole lot to him. If you're honest with yourself, you're not going to have that many special nights as an individual. I really depend on Gerry, Chip and Joe to make my music sound good. People have said weird things, like “You should never give that much solo space or attention to somebody else.” Well, man, some of the greatest players in the world are standing up there! They should play, and the people should hear them!"

Chuck lived all but two and a half of his 34 years in Rochester. His older brother, Gap, was also a musician (piano), and "he bought all the records." Chuck took his degree in Eastman, taught in parochial school for one year, then moved to New York City for the two and a half years.

His grandparents were Italian immigrants. His father formed the bridge between Old Italy and New America. He is a rare and special man, a man "totally committed to us, to his kids. He grew up just wanting his children to have the opportunities he never had." Most of all, Chuck's father allowed him and the others to truly be themselves. He never tried to force them into artificial roles of middle-class respectability.

Mr. Mangione owned a grocery store that was attached to the house. "He used to sit in the kitchen eating supper, and would run out to take care of a customer. It was a very friendly neighborhood-family situation. He would open up the store at 6:30 in the morning, finish at 11:30 at night, and then say, “What do you guys want to do? Where do you want to go?”

It wasn't as if he had initially been a music freak. He loves music - and he's the greatest dancer in the world - but he was never a frustrated musician. He wanted only for us. If we had been interested in medicine, he would have taken us to hospitals to see what was happening. But we were interested in music, so he said, "Who do you want to hear ?"

"And we would go hear somebody like Dizzy Gillespie. Father would walk up to them like he knew them all his life, and he'd say, “Hi, Dizzy! My name is Mr. Mangione, these are my kids, they play.” And before you'd know it, my father would be talking with this guy, and would invite them over for spaghetti and Italian wine, and we'd wind up having a jam session in the living room.

"Now that I think about the musicians in that house, I freak out, you know'? One afternoon there were Jimmy Cobb, Sam Jones, Junior Mance, Ronnie Zito, and Ron Carter, and we were all sitting there in my living room playing! This would happen every week. Musicians would come into town, we'd go and meet then, they'd be invited over for food, and we'd get to play."

Dizzy Gillespie also came over to the house, but I don't think he came over and played, as much as he came over and ate! We got to be really good friends, and he sent me one of those upswept horns of his. I regard him as being my musical father. He was truly an inspiration for me."

When Chuck was a boy, big bands were in - Stan Kenton, Count Basie, Woody Herman, etc. Later, he listened to beboppers Art Blakey, Cannonball Adderly. Horace Silver, Miles Davis, and Gillespie.

When he graduated from high school and attended the Eastman School of Music, "there was absolutely nothing happening there in the musical directions I wanted to follow. Jazz was forbidden. We had to rehearse in hidden corners, you know?" However, Chuck feels he was perhaps a bit narrow-minded at the time. "I did what a lot of young people do when something is not their way: I rebelled against everything. Because of that, I didn't really take advantage of the four years I spent as an Eastman student. I never studied composition, and I never studied orchestration - the very things that would have been extremely beneficial to me today.

"As it stands now, both composing and arranging are very tedious processes for me, and orchestration is a big guessing game. It's actually sitting down at the piano and pounding out voicings and trying to imagine what they will sound like. I've been very lucky. The music sounds good, and I don't apologize for anything I've recorded, but I've nevertheless been very, very lucky.

"When you're 17 or 18, you think you know all the answers - who you'll spend the rest of your life with, your religious beliefs, and exactly what you're going to be. Very positive. I was gonna be a bebop player in a jazz club. I would have committed anybody to an insane asylum who walked up to me and said, “Pretty soon you're gonna have a chance to conduct the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra.” I keep trying to tell young people to stay open to everything - music, people, feelings. To not become narrow. If you put up a shield like I did, there's no chance to learn anything, to grow."

Mangione himself later taught at the Eastman School of Music, directing the Eastman Jazz Ensemble. "When I arrived, there was only one jazz ensemble. When I left, there was a studio orchestra, a film writing course, an improvisation course, and three jazz ensembles.''

From 1960 to 1963, Chuck and Gap - The Mangione Brothers - recorded three Riverside albums: The Jazz Brothers, Hey, Baby!, and Spring Fever. Chuck also cut an album on his own, Recuerdo, for Jazzland Records.

He went to New York in 1964, freelanced with Kai Winding and Maynard Ferguson, and finally landed his boyhood dream gig: trumpet player with Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers. He stayed for nearly three years, playing with Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea who also passed through Blakey's band.

Leaving Rochester to play music was a major decision for Chuck, but an even greater decision came in 1969. At nearly 30 years of age, he finally accepted the fact that he was going to be a musician, "that that was what I was going to be doing for the rest of my life. There was no longer any reason for me to wake up every morning worrying about it, to wake up and say, `Well, how am I doing?' like comparing myself to something on the stock market."

It was in that same year that he composed Kaleidoscope. He hired fifty musicians himself, and put on a concert. That particular concert lost a pile of money, but it also led to his first record, Friends & Love. "The album was never meant to be an album. It wasn't a record date. When we performed it with the Rochester Philharmonic, all we had was a four-track tape recorder there to back up the PBS television unit that was taping it."

When it was all over, Chuck was amazed with the quality of the compositions. "I couldn't believe that nobody else was ever going to hear this music!" He borrowed seven thousand dollars from the bank, hired and paid the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, and went into the record business himself. "Everything good that's happened to us has been motivated by ourselves. We released Friends & Love locally by ourselves, just the way it finally came out of Mercury. When it started making noises in Upstate New York, Mercury came up and signed us to a four year contract."

Since that time, Hill Where The Lord Hides (from Friends) was nominated for a Grammy as Best Instrumental. His first Quartet album was nominated for Best Small Group Jazz Performance. This year, Land of Make Believe was up for two Grammies: Best Big Band Performance, and Best Instrumental Arrangement Accompanying a Vocalist (Esther Satterfield). Chuck has also created his own mail order record company, Sagoma, and has signed Gerry Niewood, Gap, and Esther Satterfield.

He does not care for teaching jazz clinics, "because everything is memorized ahead of time, and there's no education experience." But he does love teaching. The week before our talk, he had been teaching high school kids in San Francisco. "Most young people today don't get challenged. Everybody gives them the one book, the one pill, the one philosophy that's going to give them all the answers. They want to make a million dollars in six months and then get out of music.

"I think the great thing about this last week was that I saw a lot of young people fall in love with music. To me, that's the only reason to be in music, because you can't count on anything else besides that love affair. That's always gotta be going on. You gotta be prepared to scuffle financially and to sacrifice a lot of very basic things in life. I wouldn't have it any other way. You can go to some professional orchestras, and it's a fight to get those people to remember that they love music. To them, it's a factory gig. They're watching the clock, time to stop, take a break, back on, toot-toot-toot, gimme the money, go home. It can be a very painful experience to somebody who really loves music."

Chuck feels it was a lesson for those kids to see him and the other Quartet members load their own equipment. “I'm not ashamed of it, either," he says. "We don't have a roadie. That means that we leave for airports early, and haul the electric piano and bass and drums ourselves. Nobody baby sits for us. We'd rather do it that way, so we can keep playing the music we believe in. We could obviously make more bread by going in another musical direction. But we would rather forego the luxury of somebody else breaking their back for us than to pay the bread and then maybe have to compromise." Transportation costs keep climbing; clubs are not getting any bigger; and Chuck will not play the acoustically abhorrent hockey rinks. "I don't make good money yet," Chuck says quite honestly, "but I make a living and pay the rent and support my wife and two daughters. I do think there is another financial level that we will reach soon, and that will make things more comfortable for everybody."

Some people have called Chuck Mangione a "renaissance musician," and others have been even more florid in their appreciation. Many musicians hunger for such praises, and even base their entire existences on it. But Chuck maintains, "A critic's reaction is just the reaction of another human being. If he's a good critic, he's human in what he hears, and he reacts, and he does what he has to do. I read all of those things, and I know they're very important, because a lot of people read criticism as fact, rather than as one person's opinion."

Despite the pressures attending his very bright future, Chuck Mangione has maintained his psychological equilibrium so well that hostile remarks don't phase him any more than compliments.

One critic called his orchestral concerts "an emasculated, homogenized stab at mixing muzak with funk." An acquaintance of mine, Edouard, attended the Royce Hall concert with me. He was scathing in his criticism. "My God," he said. "Mangione goes for the medium-rare in everything he does. I don't know, perhaps he's a flash in the pan and has lost his magic. Maybe he's come down with a severe case of the Minnie Ripertons. Sure, he plays poignant melodies that, quote, 'generate a kind of haunting Swiss Alps feeling' - it's just another way of saying he's the suburbanite housewife's dream of a white Miles Davis. I mean, who cares?

"His sexuality has all of the rage and passion of a Continental breakfast," Edouard continued to rant. "Let's face it: Chuck Mangione's audience came to be lulled and caressed, to be held close to mama's breast, to be lovingly patted all over with Johnson's Musical Baby Powder. He picks up his horn and spills out Cream of Wheat laced with dollar signs. He is the balls and banner of the entire toast and tea set. That's who cares."

How do you deal with criticism like this, Chuck?

"I don't have to deal with it. That's one person's opinion of a situation. They're certainly entitled to that opinion."

Come on, now.

"I'm just knocked out - and the record is proving it - that wherever we go, people are enjoying the music. And everybody in the band is enjoying it. We're not playing music that we don't have a good time playing. And there's no formula, no attempt to reach a specific audience of any kind. We've just been doing what we do, and the audiences have been getting bigger, and the people are getting off on what we're doing.

But at the same time, Chuck, you got a reaction. That's not somebody who just shrugged his shoulders and said, "So what?" That's somebody who at least was touched by the music. In a way, it's a compliment: Love me, hate me, but react!"

What about that question of blandness?

"Obviously, the music doesn't feel bland to me. I write the music I feel, and I play the music I write. People have the option to call it whatever they want to."

But how do you feel when somebody talks that way about your music?

"Nobody ever likes to hear anybody dislike or object to what they do. I think that sometimes people make comments in which they're trying to be very dramatic in what they say, trying to impress other people with the style of their words. I mean, that's a very well-done piece of material there."

"True ... It's nice to have people react. Five years ago, something like that would probably have destroyed me. If what he said was true to me, I just wouldn't be able to handle it. However, when you reach the point where you're true with yourself and honest with yourself musically, then none of that carries any more weight than what it really is, just criticism. I have to live with myself everyday. I don't have to walk up to that man and explain anything to him. I just do what I do, and do it to the best of my ability. And that's me."

Somebody said you lack presence, that your main emphasis is on the preconceived aspect of the music, like classical music.

"All music that I've ever enjoyed has form . . ."

But where is Chuck?

"If a piece of music is a piece of music, there are parts of it to be played together and played well, and there are parts that leave room for improvisation. If somebody starts out with something so complex and so abstract that his improvisation is no longer abstract or complex by comparison or extension, then how will the people be able to see?

"You see, I've always loved music that had melody, that had good harmonic changes, and that felt good rhythmically. That's the kind of music I want to play. My music has form, but it does not have a formula. I want the music to have a beginning and an end. And I want it to be something so beautiful that when somebody walks out, they don't say, 'Whew! I just heard the greatest technician in the world!' I want people just to say, 'The music felt good.'"

You have a kind of intensity that comes out in those long melodic lines, Chuck, but is there in fact a lack of assertiveness?

"l think this band has more balls than any other band I've ever played with. It has the flexibility and the guts to take its clothes off in front of a thousand people and play music that is very, very simple, and then turn around and play something that is very, very hot at the other extreme.

"You can have a lot of energy, and a lot of enthusiasm, and a lot of intensity, and a lot of guts, but you don't have to be mauling somebody. Nor does it have to be intensity generated through high volume amplifiers. You don't have to throw up. You can be gentle and still be intense.

"I just think of music as being with someone you love, and how you want to be with them. That is what it's all about."