Downbeat - November 25, 1971

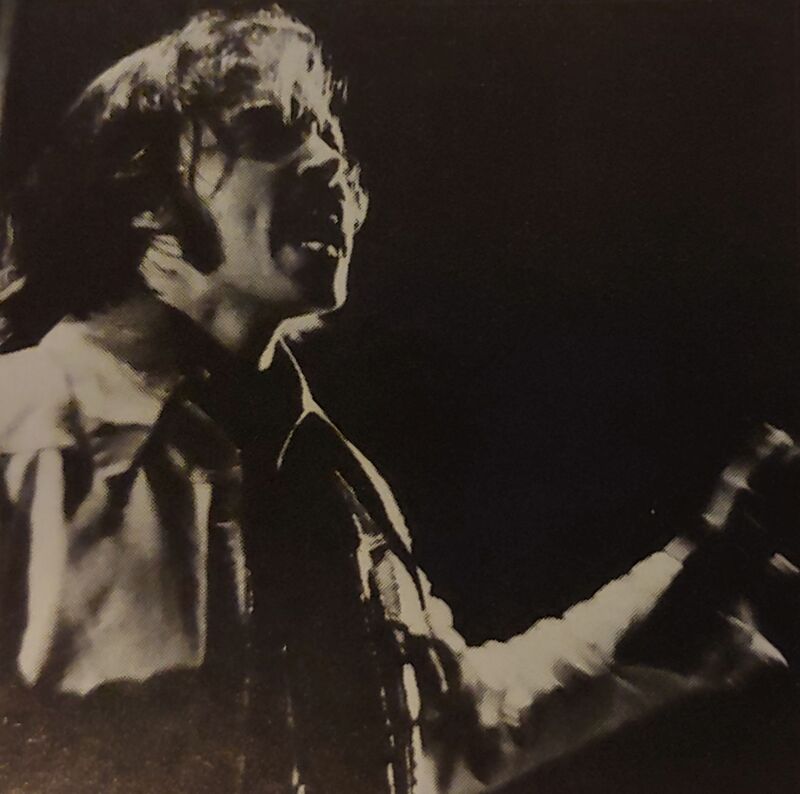

Chuck Mangione: In Love With Music

by Jim Szantor

Chuck Mangione: In Love With Music

by Jim Szantor

With his talent, flexibility and dedication, Chuck Mangione could easily succeed at any place of employment. Except, perhaps, at the U.S. Bureau of Labels and Classifications.

How he got from Point A (a young be-bop trumpeter influenced by Dizzy Gillespie), Point B (student at the Eastman School of Music), Point C (co-leading the Jazz Brothers 1960-64), points beyond (two years with Art Blakey, scoring for a rock group, a faculty position at Eastman) to Concerts A, B and C (Kaleidoscope, Friends and Love, Together) is a story interesting not only from a musical/biographical sense. Because it reveals not just a young man on the rise as an artist but a person becoming more a person/a music becoming more personal/and colleagues and friends being considered people first, "sidemen" second, with the music embracing all.

Thus Friends and Love is not only the title of his multi-idiom, mixed media nationally televised (NET) concert and subsequent Mercury album (recorded with a lot of help from those friends and the Rochester Symphony) but it is also a very fair (but only basic) measure of the man.

Though I had long admired Chuck in his formative years and still marvel at his 1962 Jazzland LP we didn't meet until recently when his visit to Chicago provided the opportunity. We met and discussed his new ecumenical approach. Here's what went down, starting with what seems like a put-on.

J.S.: . . . the Sea Shore musical aptitude test? Come on, man...

C.M.: No, it's true. I had taken that test in grade school after I had studied piano for two years. I scored high on the test and they told me to ask my parents about selecting a band instrument. Then I saw a movie that night - Young Man With a Horn starring Kirk Douglas and Harry James playing the trumpet parts - so obviously I had to play trumpet.

After about six months my brother Gap would sit down at the piano and we'd play…just play anything…some blues or something. So I was into improvising very early.

Later we had a duo together, Gap on accordion, myself on trumpet. We played weddings and won all kinds of amateur contests. At that time jazz was a very popular music. You'd hear Basie's April In Paris, Chet Baker, Stan Kenton on the radio and jukeboxes. Like at the hot dog stand across from the high school, that's what people were playing.

There was a club in town called the Ridgecrest Inn that used to bring in all sorts of people - I caught Clifford Brown, Max Roach, Horace Silver, Dizzy, Art Blakey, Kai Winding, etc. My father wasn't a musician but he was into this thing where if we were interested in medicine he would have taken us to any hospital to check things out, or if we were interested in baseball he would have taken us to see the Yankees. He'd just take us to hear anyone we wanted to hear. So we'd go meet these cats and sit in.

We'd be playing every Sunday afternoon with Dizzy - in fact that's where I got to know Dizzy and he gave me the upswept horn - and there were sessions at our house practically every night of the week. On a typical night we'd have Jimmy Cobb, Sam Jones, Junior Mance, Ron Carter, Ronnie Zito, and lots of other people. This kind of thing - which was while I was at the Preparatory Department at Eastman - happened at my house all the time.

Then when I got to my senior year in high school, Gap and I formed the Jazz Brothers with Sal Nistico and Roy McCurdy. Jimmy Garrison and Steve Davis worked with us for a while and we did those three albums for Riverside. And then the group just sort of dissolved.

J.S.: Then we lost track of you for a little while.

C.M.: Yes, because I graduated from Eastman and taught for a while in Rochester. But after a while I got the feeling that I had to go someplace and see if my own personal musical contribution was valid. After being around guys like the Roy McCurdys, the Jimmy Garrisons, the Sal Nisticos, you wonder if people are accepting you for you or just because you're associated with people that heavy.

It was a stupid ego thing but I had to find out if I could survive on my own, so I moved to New York and the people I had sat in with in Rochester turned out to be very important people. The first guy I bumped into was Kai Winding and he remembered me and gave me a gig. Then I met Mike Abene who told me Maynard Ferguson was forming the sextet. Maynard was going through a thing where he wanted to be a small group player so I was doing a few charts for that and on weekends now and then he would reassemble the 13 piece band to cover some commitments and I went out with that a few times.

I came back to Rochester for a weekend during this time and promptly got a call from Art Blakey in New York. So I went with Art for two years and recorded two albums with him. At that time we had Frank Mitchell on tenor and Reggie Johnson on bass. John Hicks had just left so Keith Jarrett was on piano. Then Mike Nock was on for a while and then Chick Corea came on the band. What a school that was! I went to school with piano players. But then after two years I couldn't handle it anymore . . . work two weeks, off a week, work a weekend, be off the week...

Mangione then returned to Rochester to write for a rock group in Cleveland, The Outsiders, that Capitol Records had just signed. He hadn't done anything in that vein and it looked like a secure thing - something like three record dates a year, good bread, and the freedom to do whatever else he had to do. But like a lot of rock groups, it got very weird and they collapsed as soon as they got big. So that didn't happen for too long of a time.

He then got back into teaching at a unique school (the Hochstein School of Music) where students pay according to their income. So if an inner-city kid could only pay 50c for a lesson, that's what he paid. They asked Chuck to set up a jazz program there and he proceeded to set up an all-city, all-county high school jazz ensemble and improvisation classes. He says it was wild to see what really young people can get into - how imaginative they can be and how easy it is to get them to play something. This experience went on for a couple of years and laid the groundwork for his position on the Eastman faculty.

While he was at Eastman, there was nothing happening at the school jazz-wise, and Mangione got his degree (B.S.) in Music Education. The trumpet feature on the "Friends and Love" album, "The Feel of a Vision", featuring Marvin Stamm, was originally written by Chuck as a graduation recital piece for another player in 1965. This cat wanted to play something that was jazz-oriented but was still entirely notated, as the school required. So Chuck improvised some things, committed them to paper and made a legitimate piece out of it. The recitalist? BS& T's Lew Soloff.

C.M.: When I got on the faculty at Eastman the first thing I tried to do was loosen things up from where they were. They had started a big band and were kind of into a formal situation where they had the band playing half a concert with the Eastman Wind Ensemble and the Jazz Ensemble was in tails. The music was rigid and they were playing some pretty dated things. In the Mood was in the library. After I took over the band, I started to loosen things up. I got the band to dress casually and at concerts, instead of a written program, I'd announce tunes like at a club - a much more intimate relationship with the audience.

Mangione really helped to turn things around. At first, the school forbade the Jazz Ensemble a full concert of their own and they were not allowed to perform in the Eastman Theater. Only after the band got going and overflowed the smaller Kilbourn Hall (700 cap.) and were regarded as a "fire hazard" were they allowed to play in the prestigious Eastman Theater, where they promptly started drawing 3500 people to concerts.

Mangione augmented the Ensemble with four French horns, three flutes, a tuba and added electricity to the rhythm section and even male and female vocalists. The jazz program continued to grow. Mangione now teaches improvisation and directs two bands and a third one is not far behind. Raeburn Wright is now the full-time head of the Department of Jazz Studies and Contemporary Media. He teaches the film writing course, advanced arranging, and has the studio orchestra (the Jazz Ensemble plus strings.)

Mangione is now a full-time faculty member himself with the title of Instructor. He has the flexibility to do what he's doing there and he also has the flexibility to leave. As a result of "Friends of Love" he's taking his quartet on a college tour and Mercury wants to record it as soon as possible.

C.M.: In taking the quartet out, I have the nucleus of my concert thing. I can take the soloists and a key player or two to a symphony orchestra and do my two concerts, either Friends or Together (which is due out shortly on Mercury as another double album). We did Friends with the Buffalo Symphony, the orchestra in Dallas definitely wants to do it and we would have done it with the Denver Symphony at Red Rock, Col. except they had a riot at a Jethro Tull thing and canceled everything and anything in any way related. I'm definitely going to take the concert to San Francisco and do it there. It's beautiful, because the concerts really are portable.

J.S.: In watching the Friends concert on TV, I found that you were quite at home in front of the Rochester Symphony. Did you have much experience beforehand in formal conducting?

C.M.: The only thing I had was the basic conducting course I had taken in Music Education, which is nothing really heavy. I think more important than knowing how to wave your arms is knowing your music thoroughly. Whatever you're working with. You don't have to be the slickest conductor in the world but you have to know how to ask for what you want. In fact, a lot of conducting is unnecessary. Like Woody Herman doesn't have to conduct, but there are times when he's important to cue or cut something off.

The same is true with 70 musicians. When the thing is fairly straight ahead and the tempo is fairly set, a lot of conducting becomes mechanical or just something to do. You're right when you say you can conduct with your eyes...I do that and I find myself grooving and dancing on the podium. If it's on you can really have a lot of fun. And I'm lucky that I'm conducting music that I've written and orchestrated so I know it backwards and forwards.

Leonard Feather probably said it best: "Mangione's undertaking ("Friends and Love") was something else. He was not out to convert the symphony into a medium for cheap exploitation. Instead, he drew on a number of moods, forms, and idioms to provide a complete concert experience."

J.S.: How did you go from playing bebop to composing, conducting and playing on something as wide open and unprecedented as Friends and Love?

C.M.: I didn't actually take my first formal training in writing until I had graduated from Eastman and studied with Raeburn Wright. For my evaluation piece I wrote something for strings, She's Gone, from the concert - written as a sax solo. It's virtually the same arrangement that's there now. So that was my introduction into writing orchestral things. I got the desire to write for strings and larger situations but I still want to keep my jazz roots. There always has to be the jazz element in it.

J.S.: The eclectic makeup of the concert really surprised me. You had the folk singers (Don Potter and Bat McGrath), your jazz soloists (Marvin Stamm, Gerry Niewood, Gap), a classical guitarist (Stanley Watson) plus the symphony orchestra...

C.M.: When someone asks you to do something as important as music is to me, like a concert that's going to take a whole lot of work, I turn to my friends - people who feel about music like I do. Don and Bat had a coffee house where I used to hang out and I would play with them and try to get into their music and they would try to get into mine. Earlier, Bat wrote lyrics to She's Gone and Don sang it at my Kaleidoscope concert. So we were always trying to make music together. And I met Stanley Watson at the Hochstein School and was amazed at his music and we did a couple of things there together, just fluegelhorn and guitar. And of course there was Gap and Gerry, from my quartet.

As for the concert, my concept was to make music with people who love music and were my friends. I figured that if everybody did what they did well, it had to work. The music was honest and everybody was going straight ahead without thinking about labels. We're trying to forget those. Labels lead to preconceived ideas.

Anyway, it took about six months to put the Friends concert together with the last piece of music being copied an hour before the first performance, and all those panics. Then we got to the rehearsal and everything went wrong. Tony Levin arrived at the first rehearsal with poison ivy on his hands. Then Gap's new electric piano arrived and wouldn't work. Then Don and Bat got lost on their way into Rochester. In all we had only three rehearsals - about eight hours to learn the whole concert.

During the rehearsals not once did we play any one piece of music on the album from beginning to end. We'd rehearse this section, go over that panic . . . The concert was videotaped and no album was intended at all. We had a four-track unit running for an audio backup for TV in case anything went wrong with their audio. What you hear on the Friends album was exactly what happened that night. Just one night. We didn't have a series of performances taped to choose the best tracks from like other bands do. One time only. But if we had done it in a studio we couldn't have improved upon the performance, just the sound.

I still don't know how it happened but it all came together and when I listened to the tapes after the concert I decided that it would be nice to have a record of if. After we got a few clearances and paid the orchestra, we put it out on Gap's label (GRC) in Rochester. Just the way it looks now - music, artwork, everything. It did well in upstate New York and Mercury heard about it, signed me to a four-year contract, took the album and shipped it out.

J.S.: It seems to have done fantastically well...

C.M.: Well, a Mercury executive and I were talking about it and if the record hadn't sold we surely would have known why. First, it's an instrumental record and that isn't much of a commercial item. Who's made it instrumentally? Herb Alpert was the last thing and what happened before that? Second, it's a double album - wrong again; too high priced. Third, I'm a new artist that nobody knows about.

But it went berserk in upstate New York. Everybody started playing Hill Where The Lord Hides as the cut - and it was a seven-minute cut. There was no single. But someone at a top 40 station in Dallas figured out a way and edited it down to a four-minute single and made it a number one record in Dallas. On that basis, Mercury then put out a single that broke number one in Buffalo, Seattle and Denver. Sales of the album, at double album price, are over 70,000 - that's equal to 140,000 albums.

J.S.: Why do you think it made it? After all, you didn't even intend to make an album, much less a hit single.

CM.: That's it, I think. We weren't sitting in a studio and listening to some producer say: "We've got to look for the hit here", or "Where's the 2:40 cut". I'd rather do the music the way I feel the music and worry afterwards about where any single is going to come from or where this or that is going to come from. Because as soon as you try to write commercially, forget it. I don't know any formulas. I just write music.

J.S.: That's really the key. You can always tell when someone is trying too hard at the wrong things for the worst reasons.

C.M.: That's why if I can't truly communicate, I don't want to play. I might as well go home and play in the living room with my quartet for personal enjoyment. To me, the greatest satisfaction in making music is getting other people off on music.

We discussed Chuck's role as an educator and the Eastman school in particular. Mangione spoke with animation and enthusiasm, but also with realism. Here are some of his observations, opinions, and comments.

If Eastman can graduate 20 teachers a year that can go out and really teach about 100 kids each, then you really have something. The whole education process has just got to come around.

All of a sudden jazz is becoming very "in" at the college level and I think it's only because rock is still outside the door right now and they can't keep everybody out. So they say, "Well, jazz has been around for a long time and we'll let that in the door." But they were afraid. Because the power to teach music so free - who do you give that strength to? Who are you going to trust? What's he going to do, turn the whole school into junkies? But I think it's changing now. But that's a whole number about young people.

I was very negative about Eastman for a long time. But I'd have to say that the direction that it's going in is a positive one. I'm really not convinced, however, that they'll ever have a jazz major, there. My concept of a good program there would be to turn out the finest musicians who have all been exposed to the best music of all bags - who are capable of handling anything when they get out of there.

In a way, music education has been dishonest. Like you go to the Eastman School for four years and you might pay $12,000 in tuition alone in four years to get a degree. So you come out with a piece of paper that say's "major in violin" and you've been sitting there four years, right? You finally graduate and somebody is surely going to tell you the chances of ever playing in a symphony orchestra are 90 to 1. So the poor cat ends up starving or teaching - as a teacher who never wanted to teach.

The first thing anyone should tell a musician is that he's never probably going to make a living in the music business. Be realistic about it. Take him out there and show him that herd of cattle at the Union Hall in New York. Man, that freaked me out when I saw that. I couldn't believe it. Everybody saying: "Hey, baby, yeah, give me your number and I'll give you my number" and all those people swarming around trying to pick up a $35 night just so they can stay alive. Who ever sees anything but the glamour side. The big concert. Guys are scuffling on the road who haven't slept in a bed for days. But nobody ever talks about that.

The only way I know to teach anybody anything - like I'm rehearsing a symphony orchestra and most of the musicians aren't very receptive to my thing - is to try to show them how much I love the music. That's the only teaching tool I have.

As pleased as he is with the album's success and his music's acceptance, Mangione is not one to stand still. His is a larger purpose.

"I've played a lot of music with a lot of people and have been satisfied, previously, with the music alone. Now I get off on people. If I see them reacting to my music, that's it. And if I can't communicate with them, that's the most frustrating thing for me because I'm now beyond playing for my own ego. To me, I don't remember that anymore. I just don't know how to do that anymore. I can't satisfy myself with a "great solo". The greatest thing for me is to communicate with people absolutely without compromise. Not writing down or anything. I just feel that now is the time for my music. What do I call it? It's me, my music, what I am, and what I've been."

What Chuck Mangione is and what he's doing is not only very beautiful in itself. Moreover, his approach to music and his love for it can only help to eradicate the illogical barriers that stubbornly persist. He's already proven that a community of artists can emerge from very diverse bags and produce great music. That's his heaviest contribution to music thus far but I'm sure there'll be many more of like proportions.

How he got from Point A (a young be-bop trumpeter influenced by Dizzy Gillespie), Point B (student at the Eastman School of Music), Point C (co-leading the Jazz Brothers 1960-64), points beyond (two years with Art Blakey, scoring for a rock group, a faculty position at Eastman) to Concerts A, B and C (Kaleidoscope, Friends and Love, Together) is a story interesting not only from a musical/biographical sense. Because it reveals not just a young man on the rise as an artist but a person becoming more a person/a music becoming more personal/and colleagues and friends being considered people first, "sidemen" second, with the music embracing all.

Thus Friends and Love is not only the title of his multi-idiom, mixed media nationally televised (NET) concert and subsequent Mercury album (recorded with a lot of help from those friends and the Rochester Symphony) but it is also a very fair (but only basic) measure of the man.

Though I had long admired Chuck in his formative years and still marvel at his 1962 Jazzland LP we didn't meet until recently when his visit to Chicago provided the opportunity. We met and discussed his new ecumenical approach. Here's what went down, starting with what seems like a put-on.

J.S.: . . . the Sea Shore musical aptitude test? Come on, man...

C.M.: No, it's true. I had taken that test in grade school after I had studied piano for two years. I scored high on the test and they told me to ask my parents about selecting a band instrument. Then I saw a movie that night - Young Man With a Horn starring Kirk Douglas and Harry James playing the trumpet parts - so obviously I had to play trumpet.

After about six months my brother Gap would sit down at the piano and we'd play…just play anything…some blues or something. So I was into improvising very early.

Later we had a duo together, Gap on accordion, myself on trumpet. We played weddings and won all kinds of amateur contests. At that time jazz was a very popular music. You'd hear Basie's April In Paris, Chet Baker, Stan Kenton on the radio and jukeboxes. Like at the hot dog stand across from the high school, that's what people were playing.

There was a club in town called the Ridgecrest Inn that used to bring in all sorts of people - I caught Clifford Brown, Max Roach, Horace Silver, Dizzy, Art Blakey, Kai Winding, etc. My father wasn't a musician but he was into this thing where if we were interested in medicine he would have taken us to any hospital to check things out, or if we were interested in baseball he would have taken us to see the Yankees. He'd just take us to hear anyone we wanted to hear. So we'd go meet these cats and sit in.

We'd be playing every Sunday afternoon with Dizzy - in fact that's where I got to know Dizzy and he gave me the upswept horn - and there were sessions at our house practically every night of the week. On a typical night we'd have Jimmy Cobb, Sam Jones, Junior Mance, Ron Carter, Ronnie Zito, and lots of other people. This kind of thing - which was while I was at the Preparatory Department at Eastman - happened at my house all the time.

Then when I got to my senior year in high school, Gap and I formed the Jazz Brothers with Sal Nistico and Roy McCurdy. Jimmy Garrison and Steve Davis worked with us for a while and we did those three albums for Riverside. And then the group just sort of dissolved.

J.S.: Then we lost track of you for a little while.

C.M.: Yes, because I graduated from Eastman and taught for a while in Rochester. But after a while I got the feeling that I had to go someplace and see if my own personal musical contribution was valid. After being around guys like the Roy McCurdys, the Jimmy Garrisons, the Sal Nisticos, you wonder if people are accepting you for you or just because you're associated with people that heavy.

It was a stupid ego thing but I had to find out if I could survive on my own, so I moved to New York and the people I had sat in with in Rochester turned out to be very important people. The first guy I bumped into was Kai Winding and he remembered me and gave me a gig. Then I met Mike Abene who told me Maynard Ferguson was forming the sextet. Maynard was going through a thing where he wanted to be a small group player so I was doing a few charts for that and on weekends now and then he would reassemble the 13 piece band to cover some commitments and I went out with that a few times.

I came back to Rochester for a weekend during this time and promptly got a call from Art Blakey in New York. So I went with Art for two years and recorded two albums with him. At that time we had Frank Mitchell on tenor and Reggie Johnson on bass. John Hicks had just left so Keith Jarrett was on piano. Then Mike Nock was on for a while and then Chick Corea came on the band. What a school that was! I went to school with piano players. But then after two years I couldn't handle it anymore . . . work two weeks, off a week, work a weekend, be off the week...

Mangione then returned to Rochester to write for a rock group in Cleveland, The Outsiders, that Capitol Records had just signed. He hadn't done anything in that vein and it looked like a secure thing - something like three record dates a year, good bread, and the freedom to do whatever else he had to do. But like a lot of rock groups, it got very weird and they collapsed as soon as they got big. So that didn't happen for too long of a time.

He then got back into teaching at a unique school (the Hochstein School of Music) where students pay according to their income. So if an inner-city kid could only pay 50c for a lesson, that's what he paid. They asked Chuck to set up a jazz program there and he proceeded to set up an all-city, all-county high school jazz ensemble and improvisation classes. He says it was wild to see what really young people can get into - how imaginative they can be and how easy it is to get them to play something. This experience went on for a couple of years and laid the groundwork for his position on the Eastman faculty.

While he was at Eastman, there was nothing happening at the school jazz-wise, and Mangione got his degree (B.S.) in Music Education. The trumpet feature on the "Friends and Love" album, "The Feel of a Vision", featuring Marvin Stamm, was originally written by Chuck as a graduation recital piece for another player in 1965. This cat wanted to play something that was jazz-oriented but was still entirely notated, as the school required. So Chuck improvised some things, committed them to paper and made a legitimate piece out of it. The recitalist? BS& T's Lew Soloff.

C.M.: When I got on the faculty at Eastman the first thing I tried to do was loosen things up from where they were. They had started a big band and were kind of into a formal situation where they had the band playing half a concert with the Eastman Wind Ensemble and the Jazz Ensemble was in tails. The music was rigid and they were playing some pretty dated things. In the Mood was in the library. After I took over the band, I started to loosen things up. I got the band to dress casually and at concerts, instead of a written program, I'd announce tunes like at a club - a much more intimate relationship with the audience.

Mangione really helped to turn things around. At first, the school forbade the Jazz Ensemble a full concert of their own and they were not allowed to perform in the Eastman Theater. Only after the band got going and overflowed the smaller Kilbourn Hall (700 cap.) and were regarded as a "fire hazard" were they allowed to play in the prestigious Eastman Theater, where they promptly started drawing 3500 people to concerts.

Mangione augmented the Ensemble with four French horns, three flutes, a tuba and added electricity to the rhythm section and even male and female vocalists. The jazz program continued to grow. Mangione now teaches improvisation and directs two bands and a third one is not far behind. Raeburn Wright is now the full-time head of the Department of Jazz Studies and Contemporary Media. He teaches the film writing course, advanced arranging, and has the studio orchestra (the Jazz Ensemble plus strings.)

Mangione is now a full-time faculty member himself with the title of Instructor. He has the flexibility to do what he's doing there and he also has the flexibility to leave. As a result of "Friends of Love" he's taking his quartet on a college tour and Mercury wants to record it as soon as possible.

C.M.: In taking the quartet out, I have the nucleus of my concert thing. I can take the soloists and a key player or two to a symphony orchestra and do my two concerts, either Friends or Together (which is due out shortly on Mercury as another double album). We did Friends with the Buffalo Symphony, the orchestra in Dallas definitely wants to do it and we would have done it with the Denver Symphony at Red Rock, Col. except they had a riot at a Jethro Tull thing and canceled everything and anything in any way related. I'm definitely going to take the concert to San Francisco and do it there. It's beautiful, because the concerts really are portable.

J.S.: In watching the Friends concert on TV, I found that you were quite at home in front of the Rochester Symphony. Did you have much experience beforehand in formal conducting?

C.M.: The only thing I had was the basic conducting course I had taken in Music Education, which is nothing really heavy. I think more important than knowing how to wave your arms is knowing your music thoroughly. Whatever you're working with. You don't have to be the slickest conductor in the world but you have to know how to ask for what you want. In fact, a lot of conducting is unnecessary. Like Woody Herman doesn't have to conduct, but there are times when he's important to cue or cut something off.

The same is true with 70 musicians. When the thing is fairly straight ahead and the tempo is fairly set, a lot of conducting becomes mechanical or just something to do. You're right when you say you can conduct with your eyes...I do that and I find myself grooving and dancing on the podium. If it's on you can really have a lot of fun. And I'm lucky that I'm conducting music that I've written and orchestrated so I know it backwards and forwards.

Leonard Feather probably said it best: "Mangione's undertaking ("Friends and Love") was something else. He was not out to convert the symphony into a medium for cheap exploitation. Instead, he drew on a number of moods, forms, and idioms to provide a complete concert experience."

J.S.: How did you go from playing bebop to composing, conducting and playing on something as wide open and unprecedented as Friends and Love?

C.M.: I didn't actually take my first formal training in writing until I had graduated from Eastman and studied with Raeburn Wright. For my evaluation piece I wrote something for strings, She's Gone, from the concert - written as a sax solo. It's virtually the same arrangement that's there now. So that was my introduction into writing orchestral things. I got the desire to write for strings and larger situations but I still want to keep my jazz roots. There always has to be the jazz element in it.

J.S.: The eclectic makeup of the concert really surprised me. You had the folk singers (Don Potter and Bat McGrath), your jazz soloists (Marvin Stamm, Gerry Niewood, Gap), a classical guitarist (Stanley Watson) plus the symphony orchestra...

C.M.: When someone asks you to do something as important as music is to me, like a concert that's going to take a whole lot of work, I turn to my friends - people who feel about music like I do. Don and Bat had a coffee house where I used to hang out and I would play with them and try to get into their music and they would try to get into mine. Earlier, Bat wrote lyrics to She's Gone and Don sang it at my Kaleidoscope concert. So we were always trying to make music together. And I met Stanley Watson at the Hochstein School and was amazed at his music and we did a couple of things there together, just fluegelhorn and guitar. And of course there was Gap and Gerry, from my quartet.

As for the concert, my concept was to make music with people who love music and were my friends. I figured that if everybody did what they did well, it had to work. The music was honest and everybody was going straight ahead without thinking about labels. We're trying to forget those. Labels lead to preconceived ideas.

Anyway, it took about six months to put the Friends concert together with the last piece of music being copied an hour before the first performance, and all those panics. Then we got to the rehearsal and everything went wrong. Tony Levin arrived at the first rehearsal with poison ivy on his hands. Then Gap's new electric piano arrived and wouldn't work. Then Don and Bat got lost on their way into Rochester. In all we had only three rehearsals - about eight hours to learn the whole concert.

During the rehearsals not once did we play any one piece of music on the album from beginning to end. We'd rehearse this section, go over that panic . . . The concert was videotaped and no album was intended at all. We had a four-track unit running for an audio backup for TV in case anything went wrong with their audio. What you hear on the Friends album was exactly what happened that night. Just one night. We didn't have a series of performances taped to choose the best tracks from like other bands do. One time only. But if we had done it in a studio we couldn't have improved upon the performance, just the sound.

I still don't know how it happened but it all came together and when I listened to the tapes after the concert I decided that it would be nice to have a record of if. After we got a few clearances and paid the orchestra, we put it out on Gap's label (GRC) in Rochester. Just the way it looks now - music, artwork, everything. It did well in upstate New York and Mercury heard about it, signed me to a four-year contract, took the album and shipped it out.

J.S.: It seems to have done fantastically well...

C.M.: Well, a Mercury executive and I were talking about it and if the record hadn't sold we surely would have known why. First, it's an instrumental record and that isn't much of a commercial item. Who's made it instrumentally? Herb Alpert was the last thing and what happened before that? Second, it's a double album - wrong again; too high priced. Third, I'm a new artist that nobody knows about.

But it went berserk in upstate New York. Everybody started playing Hill Where The Lord Hides as the cut - and it was a seven-minute cut. There was no single. But someone at a top 40 station in Dallas figured out a way and edited it down to a four-minute single and made it a number one record in Dallas. On that basis, Mercury then put out a single that broke number one in Buffalo, Seattle and Denver. Sales of the album, at double album price, are over 70,000 - that's equal to 140,000 albums.

J.S.: Why do you think it made it? After all, you didn't even intend to make an album, much less a hit single.

CM.: That's it, I think. We weren't sitting in a studio and listening to some producer say: "We've got to look for the hit here", or "Where's the 2:40 cut". I'd rather do the music the way I feel the music and worry afterwards about where any single is going to come from or where this or that is going to come from. Because as soon as you try to write commercially, forget it. I don't know any formulas. I just write music.

J.S.: That's really the key. You can always tell when someone is trying too hard at the wrong things for the worst reasons.

C.M.: That's why if I can't truly communicate, I don't want to play. I might as well go home and play in the living room with my quartet for personal enjoyment. To me, the greatest satisfaction in making music is getting other people off on music.

We discussed Chuck's role as an educator and the Eastman school in particular. Mangione spoke with animation and enthusiasm, but also with realism. Here are some of his observations, opinions, and comments.

If Eastman can graduate 20 teachers a year that can go out and really teach about 100 kids each, then you really have something. The whole education process has just got to come around.

All of a sudden jazz is becoming very "in" at the college level and I think it's only because rock is still outside the door right now and they can't keep everybody out. So they say, "Well, jazz has been around for a long time and we'll let that in the door." But they were afraid. Because the power to teach music so free - who do you give that strength to? Who are you going to trust? What's he going to do, turn the whole school into junkies? But I think it's changing now. But that's a whole number about young people.

I was very negative about Eastman for a long time. But I'd have to say that the direction that it's going in is a positive one. I'm really not convinced, however, that they'll ever have a jazz major, there. My concept of a good program there would be to turn out the finest musicians who have all been exposed to the best music of all bags - who are capable of handling anything when they get out of there.

In a way, music education has been dishonest. Like you go to the Eastman School for four years and you might pay $12,000 in tuition alone in four years to get a degree. So you come out with a piece of paper that say's "major in violin" and you've been sitting there four years, right? You finally graduate and somebody is surely going to tell you the chances of ever playing in a symphony orchestra are 90 to 1. So the poor cat ends up starving or teaching - as a teacher who never wanted to teach.

The first thing anyone should tell a musician is that he's never probably going to make a living in the music business. Be realistic about it. Take him out there and show him that herd of cattle at the Union Hall in New York. Man, that freaked me out when I saw that. I couldn't believe it. Everybody saying: "Hey, baby, yeah, give me your number and I'll give you my number" and all those people swarming around trying to pick up a $35 night just so they can stay alive. Who ever sees anything but the glamour side. The big concert. Guys are scuffling on the road who haven't slept in a bed for days. But nobody ever talks about that.

The only way I know to teach anybody anything - like I'm rehearsing a symphony orchestra and most of the musicians aren't very receptive to my thing - is to try to show them how much I love the music. That's the only teaching tool I have.

As pleased as he is with the album's success and his music's acceptance, Mangione is not one to stand still. His is a larger purpose.

"I've played a lot of music with a lot of people and have been satisfied, previously, with the music alone. Now I get off on people. If I see them reacting to my music, that's it. And if I can't communicate with them, that's the most frustrating thing for me because I'm now beyond playing for my own ego. To me, I don't remember that anymore. I just don't know how to do that anymore. I can't satisfy myself with a "great solo". The greatest thing for me is to communicate with people absolutely without compromise. Not writing down or anything. I just feel that now is the time for my music. What do I call it? It's me, my music, what I am, and what I've been."

What Chuck Mangione is and what he's doing is not only very beautiful in itself. Moreover, his approach to music and his love for it can only help to eradicate the illogical barriers that stubbornly persist. He's already proven that a community of artists can emerge from very diverse bags and produce great music. That's his heaviest contribution to music thus far but I'm sure there'll be many more of like proportions.